Disposable Humans

“Assisted suicide” continues to prosper.

Monday, October 24, 2022

By Bruce Bawer

Reprinted from FrontPageMag

Back in 2014 I wrote here about a healthy two-year-old giraffe named Marius, who, amid much controversy, was euthanized by the Copenhagen Zoo to make room for “a genetically more valuable giraffe,” as the zoo’s scientific director rather indelicately put it. An international zoo official supported his decision, saying that critics (most of them, apparently, American) should think less about Marius and more about “the bigger picture.” As I commented at the time, these two zoo folk weren’t – aren’t – alone; they belong to a contemporary breed of people, particularly thick on the ground in northern Europe, who think this way not just about animals but, yes, about human beings.

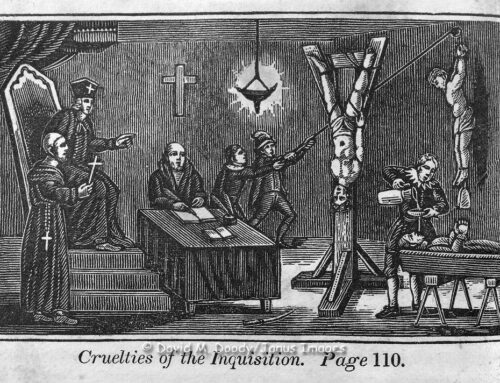

These “bigger picture” types would be quick to deny that there’s anything morally dubious about their position. On the contrary, as I wrote in my 2014 piece, they’re “certain that they are noble and good. They believe in the cycle of life. They believe in quality of life. They just don’t happen to believe in the individual life.” Often, I added, they contrast themselves to “sentimentalists” – many of them, yes, Americans – “who don’t grasp that every individual life is only part of a larger design, a ‘bigger picture,’ and should be extinguished the moment it becomes burdensome or inconvenient.” I suggested that “there exists a certain continuity between this way of thinking and that which made possible the horrors of the Final Solution.”

In 2014, “active euthanasia,” which means administering a lethal drug, was allowed in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Period. When I revisited the topic in a 2018 article, it was also permitted in Colombia and Canada. India allowed “passive euthanasia,” i.e. withholding artificial life support, while other jurisdictions – Switzerland, Germany, South Korea, Japan, and several U.S. states – prohibited euthanasia per se but allowed “physician-assisted suicide.”

On August 18 of this year, I was shocked to read in the New York Times that a friend of mine, the writer Norah Vincent, had died on July 6 at age 53. After making some inquiries, I discovered that her death had taken place at a Swiss institution specializing in assisted suicide. Norah, whom I’ve already written about at length, wasn’t physically ill or in physical pain when she chose to die; she doesn’t even seem to have been racked by deep depression. In her final days she was able to laugh and joke; in the very last picture of her, taken the day before her death, she has a big smile on her face.

But then perhaps she was in such good spirits precisely because she knew she was about to go. Norah had long been fascinated by death. In her last moments she thought she was embarking on a great adventure. Those of us who can’t relate to such feelings – who find them more terrifying than the scariest movie ever – are very, very lucky.

After my article about Norah’s death appeared, I received a Facebook message from a stranger in the Netherlands whose mother had chosen to be euthanized when she was dying of cancer. This woman felt that I’d been too critical of assisted suicide. In fact I’d tried to focus my piece on Norah and not on my own views. I’ve had beloved pets “put down” or “put to sleep,” as they say, when they were dying and in pain. I can’t criticize human beings who, under such circumstances, want the same option for themselves.

But what about Norah’s case? I admitted to this woman that I was troubled by Norah’s choice – but I would never condemn her for it, or condemn Norah’s and my mutual friend who had traveled to Switzerland with her to be present at the end. How could I dare to? Yes, I wrote, “the idea of it still chafes against ideas about the sacredness of life that I was brought up with. As someone who’s had loved ones with serious psychiatric problems, I can’t help feeling that with better psychiatric care Norah might still be alive, and happy.” Then again, I hadn’t been in touch with Norah for many years; meanwhile our mutual friend, a brilliant, good, and sensitive woman, had been extremely close to her, and she’d concluded that Norah was living with an increasingly malignant psychic demon that would never let her go.

No, I wouldn’t ever criticize Norah or our mutual friend. But the people who agitate to legalize “assisted suicide”? The people whose chosen profession it is to “assist” at these suicides, and then go home to have dinner with their loved ones? And the people, some of them doctors and psychiatrists, who’ve even been known to suggest assisted suicide as an option to people in need of medical or psychiatric care? Them I’ll criticize.

In Norway, where I live, assisted suicide is still illegal. But “death panels” are a reality, with certain expensive life-or-death treatments being routinely denied on account of cost. Over the years there have been debates about the morality of further rationing medical procedures. Every now and then there’s an op-ed or TV debate on the question: “How much is an extra year of life worth?” Now, the reason why northern European welfare states instituted sky-high tax rates in the first place was so that there would never have to be such debates. Then Norway started pouring millions of dollars every year into the coffers of the UN and other pernicious international organizations as well as into the pockets of Third World dictators. Then there are the ever-growing number of immigrants who arrive at Oslo airport with their hands out, and the tons of cash the government gives to mosques run by hate preachers. If the people who wrote government budgets had their priorities in order, there wouldn’t be a need for debates about the cost of health care.

What these debates remind us is that the ultimate danger of permitting euthanasia and assisted suicide is that a choice that’s now being made by patients may sooner or later be made by government officials or hospital authorities against the will of patients. On the road to that hell, moreover, there’s a point beyond which people who aren’t as fiercely determined to die as Norah was are cajoled into doing so. Nor is it unreasonable to worry that a greater legitimization of suicide will make it look attractive to people who otherwise would never have contemplated it. (If this sounds unlikely, look at the countless young people who in the last few years have been seduced by the transgenderism trend.)

No country on earth, perhaps, has traveled further down this road than Canada, which has allowed assisted suicide since 2016. Last year, according to an October 11 article by Rupa Subramanya, assisted suicide accounted for more than 3% of deaths in Canada, and nearly 5% in Quebec and British Columbia. (“Progressive Vancouver Island,” Subramanya writes, “is unofficially known as the ‘assisted-death capital of the world.’”) More and more Canadians under age 45 are choosing to die in this fashion, and doctors have increasingly broadened the range of people whom they consider acceptable candidates for death. Next year, Canada’s federal government “is scheduled to expand the pool of eligible suicide-seekers to include the mentally ill and ‘mature minors.’” Subramanya recounts the alarming story of an Ontario woman, Margaret Marsilla, who discovered a few weeks ago that her 23-year-old son, Kiano Vafaeian, blind in one eye owing to diabetes, had scheduled a September 22 appointment with a doctor named Joshua Tepper to end his life. When Marsilla went public with the details, Dr. Tepper canceled the appointment.

A Toronto oncologist named Ellen Warner told Subramanya that, as “an old-fashioned Hippocratic Oath kind of doctor,” she’s “100 percent against” physician-assisted suicide. Ponder that for a moment: “old-fashioned Hippocratic Oath kind of doctor.” The Hippocratic Oath was good enough for Hippocrates (born about 460 B.C.) and it was good enough for my father and his entire generation of doctors; but now it’s “old-fashioned.” Indeed, Subramanya spoke with another physician, British Columbia psychiatrist Derryck Smith, who views the rise in Canadian deaths from assisted suicide as a positive development and who told Subramanya that he “never took the Hippocratic Oath…because he thought it was ‘archaic.’”

Subramanya also quotes Canadians whose suicide plans are based at least in part on financial considerations. Assisted suicide, one of them told her, “is the new society safety net”; another said that her daughter had told her that, given their budget problems, they wouldn’t be able to get by and would have to apply for assisted suicide.

The people applying to die aren’t the only ones who are thinking about money, of course. For government officials in Canada, as for their counterparts in other countries, assisted suicide is a splendid way to reduce health-care costs. It’s thrifty. It’s green. It helps, as Ebenezer Scrooge might put it, to “reduce the surplus population.” And even as the elites increasingly encourage the rabble to throw in the towel, those elites themselves will continue to fly halfway around the world, if necessary, to get the best treatment for their own ailments. Last month, Canadian newspapers reported a story that wasn’t the first – and won’t be the last – of its kind: a veteran who’d applied to Veterans Affairs for treatment for PTSD and a traumatic brain injury was instead offered the option of assisted death.

One critic of assisted suicide, Norwegian author Jan Grue, wrote a novel called Det blir ikke bedre (It Won’t Get Better, 2016) in which he imagines a future Norway that aims to be “the best of all possible societies.” To that end, the state incentivizes unhappy people to avail themselves of the opportunity to be put to sleep. The utilitarian mentality that is widespread in countries like Norway, Grue warned in an interview, can reinforce the notion “that there are many lives that are not worth living.” Making the opposite argument was the movie Me Before You, also from 2016 (and based on a 2012 novel by Jojo Boyes), in which Will (Sam Claflin), an athletic banker, is rendered quadraplegic by an accident. When his young carer, Louisa (Emilia Clarke), learns that he intends to undergo assisted suicide, she tries to bring meaning to his life and change his mind. They fall in love – but Will goes ahead with his plans nonetheless, because, we’re meant to understand, in the long run she’ll be better off without him.

As Jan Grue has commented, this film’s message is “that disabled people should die so other people can be grateful to be alive.” Is this really the direction in which the Western world wants to go? Let’s hope Me Before You’s overwhelmingly glowing audience reviews on Rotten Tomatoes (“most amazing film ever,” “loved it,” “I cried,” etc.) are merely reflective of the callow tastes of a certain kind of filmgoer, presumably young, dumb, and female, and not representative of the broader public’s real view of the disposability of physically imperfect human beings. In any event, at a time when more and more Americans – including mainstream political leaders – apparently support abortion right up to the moment of birth, I suppose it shouldn’t be surprising that many of the same people consider adults to be disposable as well.

This Young Woman Survived an ISIS Attack. Then She Was Euthanized in Belgium.

October 18, 2022

Reprinted from The Washington Stand

Seventeen-year-old Shanti De Corte was waiting to board a plane headed to Italy for a school trip in 2016 when an explosion went off in the Brussels Zaventem Airport. Parts of the airport filled with smoke and panicked people started running before a second bomb went off a few minutes later. Thirty-two people were killed in the airport and the corresponding attack at a metro station that day, both claimed by ISIS. Earlier this year, the then-23-year-old chose to commit suicide through euthanasia. This controversial case in Belgium is sparking well-deserved increased scrutiny on the country’s euthanasia law.

Though she did not sustain any physical injuries, the trauma of the Brussels terror attack event proved too emotionally difficult for her. De Corte had previously been admitted to a psychiatric hospital before the attack and had battled a few bouts of depression, which intensified in 2020. She eventually requested to be euthanized, citing a mental health problem. Initially, doctors denied this request. When De Corte approached a pro-euthanasia activist group, they helped her find two psychiatrists who signed off on her request to die. She was euthanized on May 7, 2022.

De Corte’s parents supported her request to be euthanized. Her mother Marielle told The Daily Mail, “It was Shanti’s wish. I am convinced she is at peace now. It brings us comfort, makes it more bearable, to know that it is what she wanted.” Yet, De Corte’s suicide has disturbed many, including neurologist Paul Deltenre who argued that physicians had failed to explore all of De Corte’s treatment options.

Belgium has one of the most liberal euthanasia laws in the world. Someone may legally request to be euthanized if they are “in a medically futile condition of constant and unbearable physical or mental suffering that cannot be alleviated, resulting from a serious and incurable disorder caused by illness or accident.” A 2015 article from The New Yorker exposes the ever-expanding list of ailments for which physicians in Belgium will allow euthanasia, including autism, anorexia, chronic-fatigue syndrome, blindness coupled with deafness, manic depression, and what the chairman of Belgium’s Federal Control and Evaluation Commission, Wim Distelmans, calls being “tired of life.”

With such broad justifications, Belgium’s skyrocketing euthanasia numbers should come as no surprise. More than 27,000 people have died from euthanasia in Belgium since it was legalized in 2002. In 2021, it was estimated that nearly one-in-five people euthanized were not likely to die naturally in the immediate future.

Research from ADF International indicates that “where euthanasia and assisted suicide are legalized, the number of people euthanized, and the number of qualifying conditions increase with no logical stopping point.” They point to Belgium as an example. In 2014, Belgium’s euthanasia law was expanded to include children without any age limit as long as they have parental consent. In 2020, the law was further amended again to eliminate conscience protections for physicians who don’t want to practice or refer patients who seek to be euthanized and normalize euthanasia as a medical procedure.

Activists fighting for the expansion of euthanasia and assisted suicide often push the narrative that these premature killings offer “death with dignity” to suffering patients. But hardships in life and health do not strip people of dignity. Indeed, when a government agrees with the false notion that someone is better off dead and helps facilitate their death, that does grievously violate one’s human dignity.

Deputy Director of ADF International Robert Clarke argues that when a government legalizes euthanasia, it sends a deeply damaging message to its citizens. He writes, “It says that at some point, a life is just no longer worth living. It speaks of lethal fatalism instead of hope to people who are struggling.” To give up on the futures of those who might be persuaded to give up on themselves will never be the answer. Instead, we must love people well by providing everyone with the best medical care, emotional and spiritual resources, and community support possible until their lives come to natural ends.

Sadly, rather than affirm the value of De Corte’s life, Belgium aided ISIS’s goal on that fateful day in 2016 by ending the life of this young women who initially survived their brutal attack. As De Corte’s story hits the news in Europe, it should be a wake-up call for all of us. The legalization of euthanasia and assisted suicide is an ugly assault on human dignity for the most vulnerable — one that must be uprooted. Tragic stories like that of Shanti De Corte ought to renew our resolve to embrace our neighbors who might be hurting and remind them that life is worth living.

Arielle Del Turco is Assistant Director of the Center for Religious Liberty at Family Research Council, and co-author of “Heroic Faith: Hope Amid Global Persecution.”

RELATED:

Lancet echoes concerns about Canada’s ‘normalisation’ of euthanasia

Bioethicist: “Legalising assisted suicide will lead to euthanasia”

In Canada, Euthanasia for “Mature” Minors?

Could euthanasia be legalised this year in the U.K.?

The Netherlands approves euthanasia for children under 12-years-old

Allow euthanasia for healthy over-75s, says Dutch MP

Assisted suicide Bill makes death a ‘treatment’ for the vulnerable

Assisted suicide push stirs fear in the hearts of disabled people

New York State considers legalising assisted suicide

‘Vulnerable at risk from change to assisted suicide laws’

Leave a Reply, please --- thank you.