Tate & Lyle tin© Provided by The Telegraph

And America too…

Britain will pay a high price for abandoning its Christian heritage

February 21, 2024

By Giles Fraser

Reprinted from The Telegraph

Samson gave the Philistines a riddle. “Out of the eater came something to eat, out of the strong came something sweet.” The Philistines couldn’t get it. And neither, it seems do our modern day Philistines – despite the fact that generations before them will have been brought up on Biblical stories like this.

Samson kills a lion with his bare hands and a swarm of bees make honey in its carcass. That’s why since 1888 Tate & Lyle’s Golden Syrup used to have a picture of a dead lion with bees buzzing over it – and it is in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s oldest unchanged brand. Abram Lyle was an elder of the Presbyterian Church in Scotland. He knew his Bible and so did the people who poured his product over their porridge and sponge puddings.

But no longer. The famous lion and bees image has been replaced with a generic – or “fresh, contemporary” in the words of the Tate & Lyle brand director – design. The lion has been re-invented, the Christian symbolism lost. As one marketing expert put it: “The story of it coming from religious belief could put the brand in an exclusionary space, especially if it were to go viral on X or TikTok”. Samson also slew a thousand Philistines with the jawbone of an ass. This kind of statement makes me want to reach for one myself.

In and of itself, I suppose this kind of thing doesn’t matter all that much. It’s only flavoured sugar syrup after all – and I’m a diabetic. Christians often over-react to perceived slights and are seen as being petty. So I will put my jawbone down. But nevertheless, it presses many of our buttons because it is still indicative of a depressing new kind of philistinism that has become all too prevalent – the idea that if cultural references have some religious dimension, they are to be deleted from a supposedly inclusive space.

The secular used to mean a place where all faiths and none were encouraged to flourish. But it has now morphed into a place where religion is to be written out of the public sphere. Samson is common to Jews and Christians. And whilst he is not specifically mentioned in the Koran, he is revered in Islamic tradition as Sham’un. Figures like Samson are common threads that tie together otherwise very different religious traditions. Yet in the name of inclusion a whole world of cultural references are to be excluded – because they are exclusionary, apparently. The logic here is crazy.

It also matters that in a post-Christian world the Bible is no longer appreciated as a common frame of cultural reference – because without a basic knowledge of Bible stories, a great deal of our inherited culture just doesn’t make any sense. Even to those who didn’t go to church, Bible stories were required reading, vital to understand Shakespeare and Milton and Handel and most of the paintings in the National Gallery.

The irony is that so-called identity politics so often takes an axe to the roots of our identity. For who we are is not just something we magically dream up in a cultural vacuum, but grows out of a thousand thousand inherited cultural reference points, laid down over time. These form the background against which things make sense. Of course, tradition must not become a kind of cultural prison. And a vigorous culture reinvents itself all the time. But the idea that we might wipe away the West’s most formative cultural influence, Christianity, in the name of inclusion, threatens to create a generation of restless, rootless wanderers, for whom the building blocks of their own identity come to be little more than ever transient popular culture and, even worse, simply how they feel. And this is the very essence of what we call philistinism.

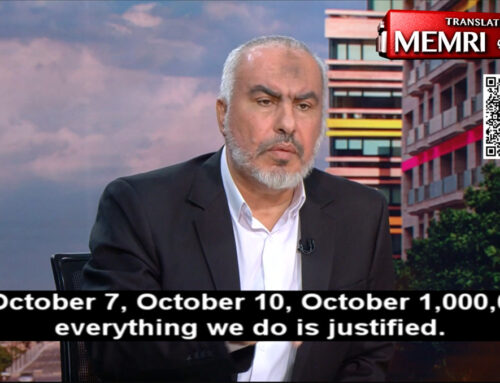

So, the dead lion matters. The use of philistine as a pejorative in the English language dates back to the Anglican cleric Matthew Arnold who also wrote about the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of “the sea of faith.” This famous poem, On Dover Beach, ends with a warning as to what a post-Christian culture might look like: “Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, Where ignorant armies clash by night.” Sounds a bit too much like the place we find ourselves in today.

Leave a Reply, please --- thank you.