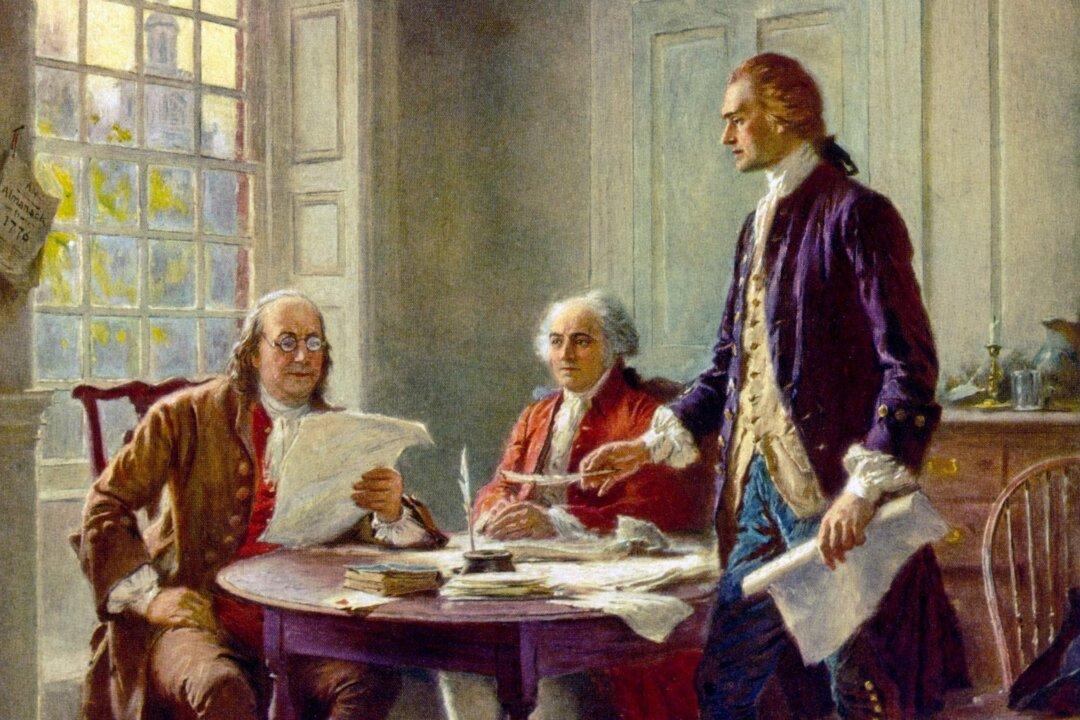

“Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776” by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, early 20th century. The oil painting depicts (L–R) Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. Public Domain

How Virtue Sustains the Individual and a Nation, According to Our Founding Fathers

The president and CEO of the National Constitution Center discusses how virtue guided the Founders and why it is imperative that America reclaim her roots.

8/8/2025

By Dustin Bass

Reprinted from The Epoch Times

Jefferson’s draft was discussed, debated, and edited over the coming days by the other members of the Committee of Five, which included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston; and then by the Second Continental Congress. When it came to those “inalienable rights,” the men, whom posterity would herald as the Founding Fathers, understood perfectly what was meant by life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The last of these three, however, has, over the last century, been slowly and completely redefined.

Jeffrey Rosen, the president and CEO of the National Constitution Center, has been working tirelessly to bend the American conscience back into its original shape regarding the meaning of happiness. Through the Constitution Center, the Congress-sponsored “We the People” podcast, and numerous annual lectures, Rosen has led the charge to help educate everyday Americans on the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. And he has done what many of the Founding Fathers did to substantiate their arguments: put pen to paper.

Defining Happiness

In his book “The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America,” Rosen defines how the Founders understood the meaning of happiness, and how their definition was not of their own creation, but rather had been concretely formulated over the millennia.

“To the Founding Fathers, the pursuit of happiness meant being good, not feeling good—the pursuit of virtue and not the pursuit of immediate pleasure,” Rosen explained. “By virtue, they meant self-mastery, self-reliance, character improvement.” This sort of “ordered liberty,” as he termed it, when someone orders his or her life virtuously and responsibly, “is a crucial part of the exercise of virtue.”

Rosen posited the Founders’ argument that, in order for a society to be free, that society must be virtuous. Their definition of happiness was based on Samuel Johnson’s dictionary, which cited numerous sources to define the word, ranging from the theologian Richard Hooker to the political philosopher John Locke. Rosen added that those ideals, coinciding in the 18th-century definition, originated from Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics.” Aristotle, as Rosen summarized, “defines happiness as an activity of the soul in conformity with excellence, or virtue.”

An engraving of Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) from “Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae,” 1553. Public Domain

A Government to Reflect the Individual

The individual objective for the Founders was the pursuit of happiness, that is, virtue—or, in the broader context, self-government. Self-government lent itself to the Founders’ overarching objective, which was to establish a government that reflected the ideals of the virtuous person.

“The Founders believed that personal self-government was necessary for political self-government,” Rosen said. “Every individual has to find the same prudence, temperance, courage and justice—which are the four classical virtues—in the constitution of their own mind, in order to achieve the same balance and harmony in the constitution of the state.”

A proper government has to come from the bottom up and not the top down. A reasonable people can articulate and therefore formulate a reasonable government. Furthermore, reason stems from a person’s rationale, and a rational person has his or her reason founded on established principles. Without reason, mankind’s form of government would be no different from that of the animals’.

As Rosen pinpoints, humans’ rights come from God. “Once society loses the sense that our rights and responsibilities come from God or nature, then everything reduces to politics, and politics, unrestrained by principle, which our Founders understood, can lead to violence.”

Rosen’s fear is that America is on the cusp of doing just this. Most of the country’s talking points, even those concerning unalienable rights, have been reduced to politics. But he indicated that this is not a 21st-century phenomenon. The Founders were well versed in failed governments of the past. In order to establish a government that would last, it was imperative to understand what caused others to collapse.

When delegates from across the states, sans Rhode Island, gathered in Philadelphia for the Constitutional Convention of 1787, each of them brought his own approach to “constitution-making.” It became a summer-long debate, grounded in the principles of reason and virtue. Rosen noted how James Madison arrived in Philadelphia with a “trunk full of books about the failed democracies of Greece and Rome.” Rosen added that John Adams considered the cycles of history to be identified by Polybius, who said “that monarchy always turns to tyranny, aristocracy to oligarchy, and democracy to the mob.”

Ultimately, however, the Founders knew that this new government established by a new constitution had to originate from the voice of the people. It had to be democratic, but constructed in a way that would temper factionalism and ensure democracy did not descend into mobocracy. The Constitutional Convention, therefore, promised a “republican form of government,” which was accepted, and the Constitution, constructed to “separate powers in order to protect liberty and guarantee the ultimate sovereignty of ‘We the People,’” was ratified by the states.

Our Fall From Virtue

Yet now, less than a year from America’s 250th anniversary, the country is split into factions, and reason is rare. Rosen argues that our reduction to politics is not a product of the 21st century, but a product of the century before. In his book, he argues that this decline in American virtue began in the 1950s and 1960s.

“Most notably we see that pop culture began to celebrate hedonism rather than self-mastery. As a result, the idea of happiness as a virtue fell out of our popular consciousness.”

The causes are complicated and multiple, ranging from new philosophies, like Romanticism, which “exalts self-expression and autonomy rather than self-mastery”; the loss of trust in traditional institutions; and “the changing role of religion in public life.” He added that the increase of technology has greatly contributed to the multi-decade decline in individual, and therefore national, virtue.

“The greatest challenge to the Founders’ idea of virtuous self-mastery and delayed gratification is our screens,” Rosen stated. As citizens become addicted to their devices—“spending more time browsing and scrolling instead of deep reading—we run the risk of becoming enslaved by our passions rather than masters of them.”

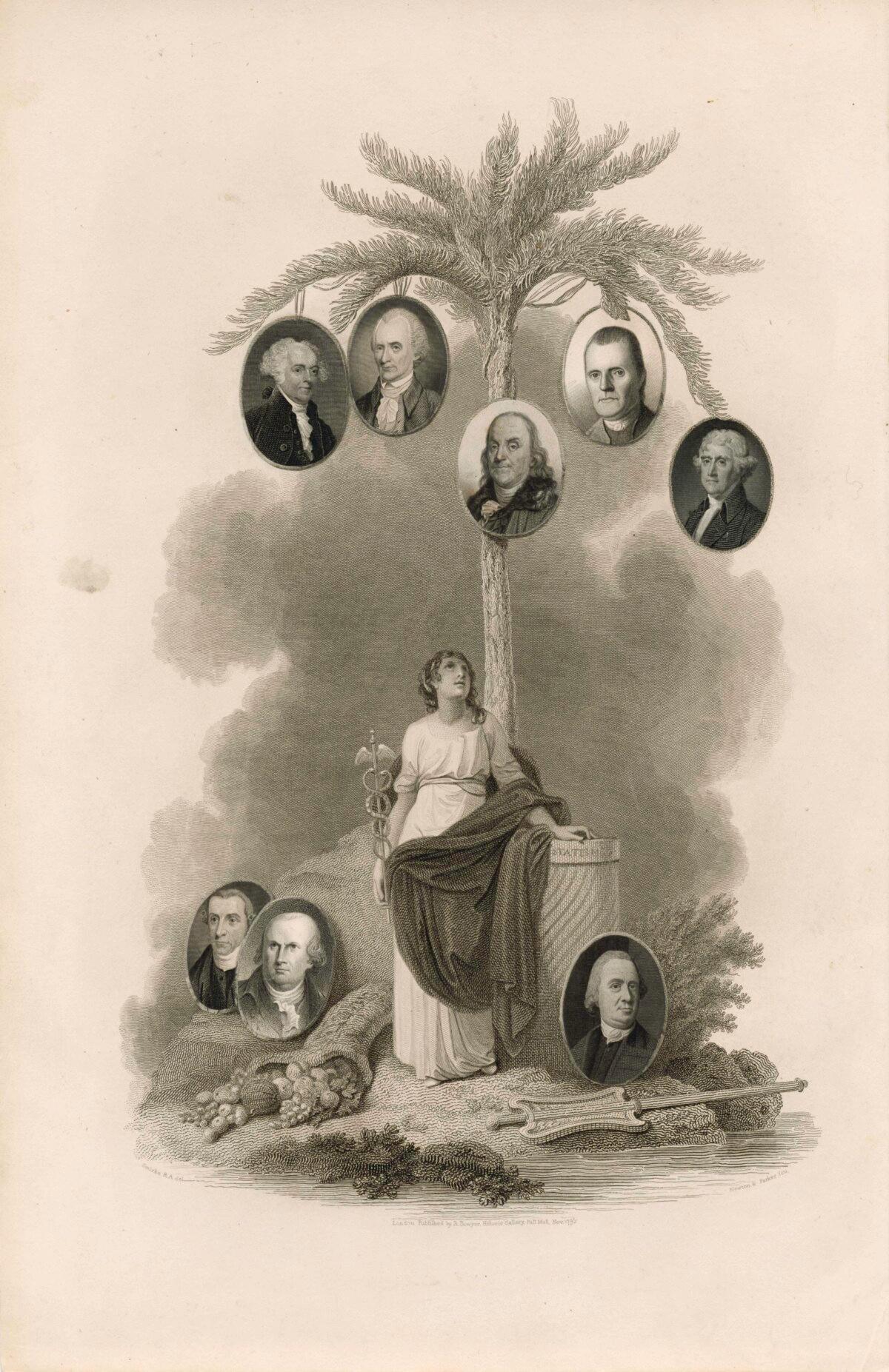

The statesmen pictured (top L–R) John Adams, Richard Henry Lee, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, Thomas Jefferson, (bottom) Patrick Henry, Robert Morris, and Samuel Adams—were all notable framers of the Constitution. Public Domain

It wasn’t solely the Founders who understood the importance of deep reading. The era’s average American citizen understood it too. This is why the Federalists and Anti-Federalists used periodicals to make their cases for or against the new constitution. Their fellow citizens read, contemplated, and, possibly, debated the ideas.

Inspired by Failure

A very far cry indeed. Social media and around-the-clock news sources, Rosen argued, “gratify the basest emotions like anger, jealousy, and fear, and negative polarization.” It’s a technology that the Founders could have never foreseen, but it’s a problem they were highly familiar with. Considering this problem, Rosen added that the Founders were “not at all sure that the American experiment [would] succeed, but they [thought] that everything turns on the virtue of citizens—the ability of citizens to find the self-mastery and self-discipline to be governed by reason rather than passion.”

Rosen fully believes that America is capable of returning to its virtuous roots. In fact, the Founders’ moral failings in their pursuit of happiness provide encouragement. Some of the most prominent Founders were slaveholders. Rosen noted that these Founders didn’t attempt to justify slavery. They believed it violated the Bible and the natural law, but it was a vice that many could not constrain.

“In a sense, it is both daunting and encouraging to see these great Founders falling short of their own ideals, because it makes us understand that we ourselves will never succeed in becoming perfect, but we can try, and we can be inspired by their exhilarating efforts,” Rosen said.

“They were so mindful about the quest. They were so morally serious in holding themselves accountable, beating themselves up when they failed to achieve their ideals, acknowledging their hypocrisies in some cases, and always trying to do better.”

A Recommitment to Virtue

Rosen suggested that we can find ourselves in the Founders because we’re not so different. Even our political discourse, as Rosen noted, is similar. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson’s debate “over national power versus states’ rights, a strong executive versus a strong Congress, liberal versus strict construction of the Constitution, has defined … our political and constitutional battles ever since.” He added, however, that although those two perennial Founders disagreed on policy, they remained committed to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Rosen strongly advocates that we do the same.

“Today it is inspiring to see that Americans of different perspectives continue to embrace the principles of the Declaration and Constitution,” he said.

“It is also sobering to note that there are illiberal forces on the Left and the Right that reject those principles. And it is urgently important, as America’s 250th anniversary approaches in 2026, that all Americans of diverse perspectives recommit ourselves to upholding the principles of the Declaration and the Constitution. It is what will ensure the continued success of the American experiment for the next 50 years and beyond.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.