Local residents burn paper offerings as a ritual for deceased ancestors during the Zhongyuan Festival in Rongan, China. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Measuring Religion in China

Many Chinese adults practice religion or hold religious beliefs, but only 1 in 10 formally identify with a religion

August 30, 2023

From Pew Research Center

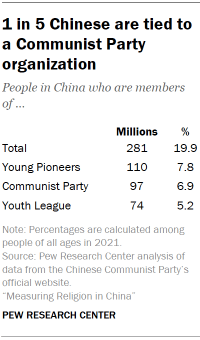

By virtue of its huge population, China is important to any effort to assess global religious trends. But determining how many people in China are religious today, and whether their religious identities, beliefs and practices have changed over the past decade, is difficult for many reasons. The challenges facing independent researchers include not just the Chinese government’s tight control of information and the Communist Party’s skepticism toward religion, but also linguistic and conceptual differences between religion in East Asia and other regions.

Because Pew Research Center has not conducted its own survey about religion in China, the Center’s demographers combed through data from various other sources – primarily surveys run by Chinese universities – to discern recent trends.

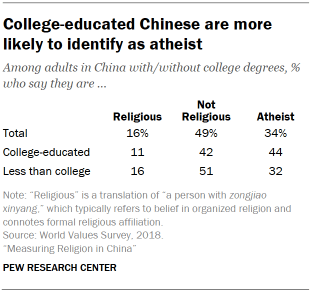

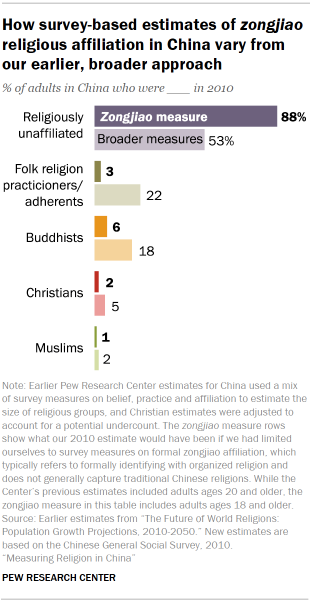

Depending on the source used, estimates of the share of Chinese people who can be described as religious in some way – because they identify with a religion, hold religious beliefs or engage in practices that have a spiritual or religious component – range from less than 10% to more than 50%.

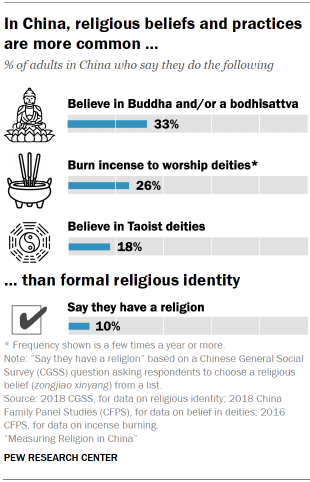

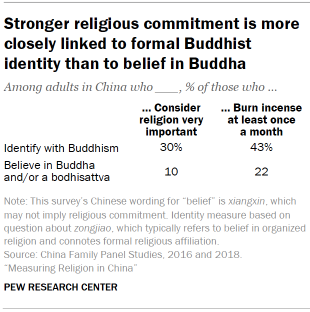

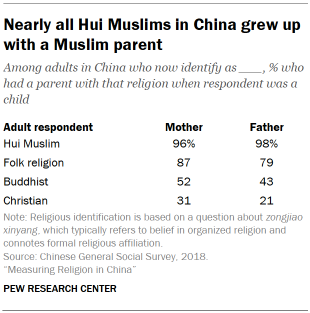

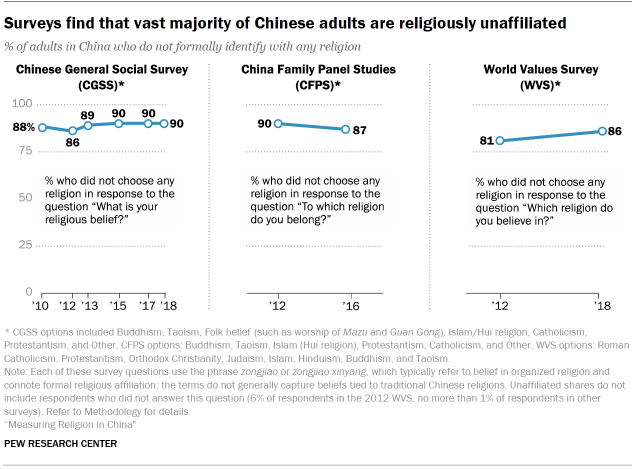

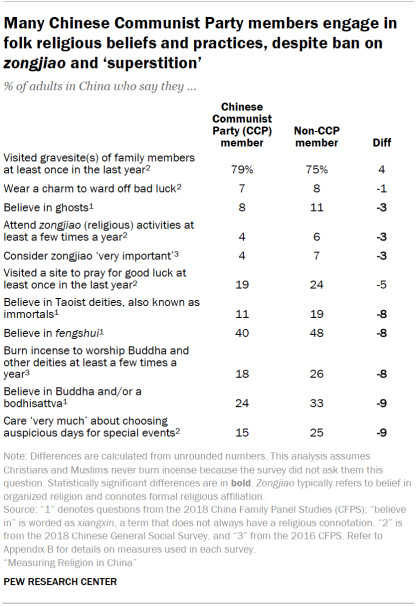

For example, only 10% of Chinese adults identified with any religious group in the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS).1 The Chinese language wording of this question – “What is your religious (zongjiao 宗教) belief (xinyang 信仰)?” – is understood in China to measure formal commitment to an organized religion or value system. Similarly, just 13% of Chinese adults say religion (zongjiao) is “very important” or “rather important” in their lives, according to the 2018 World Values Survey. Although these measures have fluctuated over time, none have clearly risen over the last 10 to 15 years.

On the other hand, surveys indicate that religion plays a much bigger role in China when the definition is widened to include survey questions on spirituality, customs and superstitions.

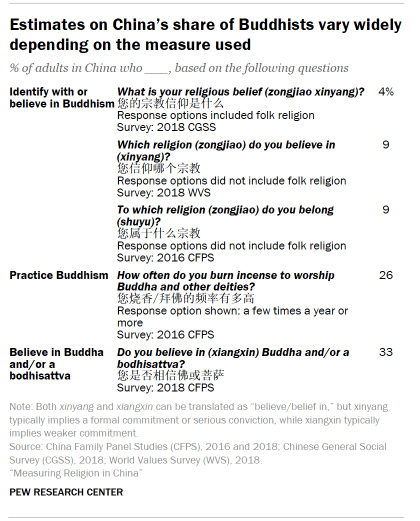

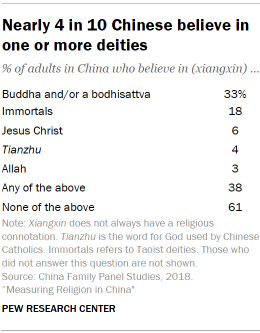

For example, 33% of Chinese adults say they believe in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, according to the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) survey.2 The 2016 CFPS shows that 26% of Chinese adults burn incense at least a few times a year – a practice that, in China, typically involves making wishes to Buddha, a bodhisattva or other deities and often indicates hope in divine intervention.3 However, just 4% of Chinese adults claim Buddhism as their religious belief (zongjiao xinyang), according to the 2018 CGSS.

What ‘religion’ means in China

The discrepancy is partly due to linguistics: The closest translation of the English word “religion” in Chinese is zongjiao, a term Chinese scholars adopted in the early 20th century when they were working with Western texts and needed to translate “religion.” To this day, zongjiao – like the terms shūkyō in Japanese and jonggyo in Korean – refers primarily to organized forms of religion, particularly those with professional clergy and institutional or governmental oversight. Zongjiao does not typically refer to diffuse religious beliefs and practices, which many Chinese people consider to be matters of custom (xisu 习俗) or superstition (mixin 迷信) instead. (For more explanation of Chinese terms used in this Overview, refer to the Key terms section.)

Moreover, many Chinese people’s understanding of zongjiao may be influenced by the government’s view that religion reflects a backward mindset incompatible with socialism. In state media, for example, the term zongjiao is used alongside superstition to indicate corruption and wavering loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party.

But there is another reason why it is hard to pin down the number of people in China who are religious. It is a conceptual problem: Western definitions of religion and measures of religious participation – such as attendance at congregational worship services – fit the monotheistic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism but are less suited to traditional beliefs and practices in East Asia.

In China, as well as in neighboring countries such as Japan and South Korea, there are many beliefs (such as in spirits) and practices (such as visiting shrines and making offerings to ancestors) that might be considered religious, broadly speaking. But there is little emphasis on membership in congregations or denominations, except among Christians and Muslims in these countries.

In East Asia, the boundaries between philosophical, cultural and religious traditions – such as Buddhism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Taoism and folk religions with local deities and regional festivals – are often unclear. People may practice elements of multiple traditions without knowing or caring about the boundaries between those traditions, and often without considering themselves to have any formal religion.4

Government restrictions on religion

Another challenge in measuring religion in China is that some affiliations, beliefs and practices are less officially acceptable than others – and thus, presumably, less comfortable for Chinese people to disclose in surveys.

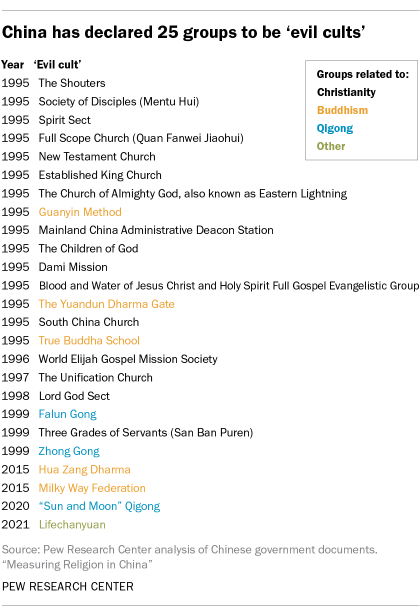

Although the government formally recognizes five religions – Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam, Protestantism and Taoism – it closely monitors their houses of worship, clergy appointments and funding. Many activities that could help to maintain or expand these five zongjiao groups are banned, including proselytizing and organized religious education for children, such as Sunday schools or religious summer camps.

Enforcement has varied over time and by province, but since President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, local officials have been less likely to overlook such activities. Religions that are not officially recognized, including those practiced mainly by ethnic minorities or foreigners, also are subject to a host of controls. Some groups, such as Falun Gong (法轮功), are completely banned.

(For more detail, read the section on how Chinese government policies toward religion have changed in recent decades.)

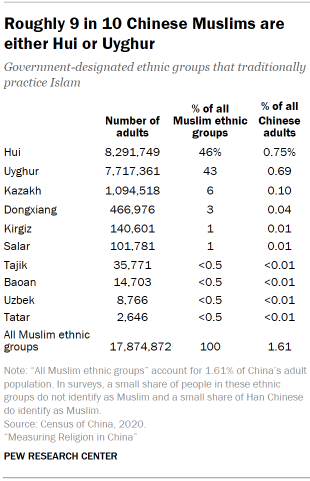

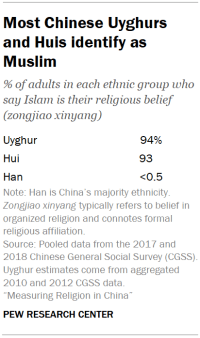

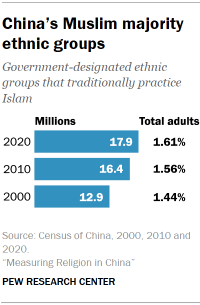

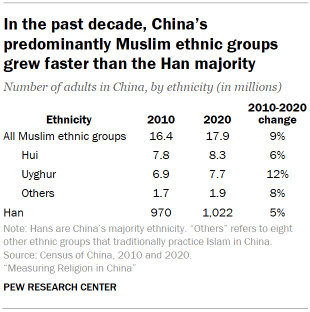

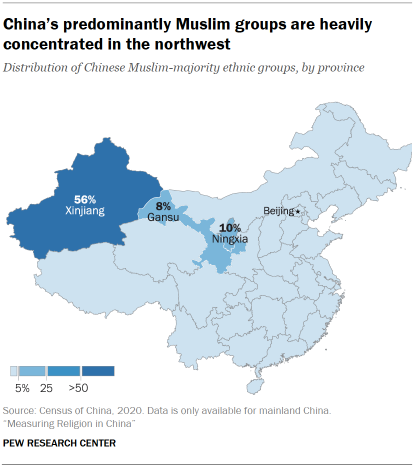

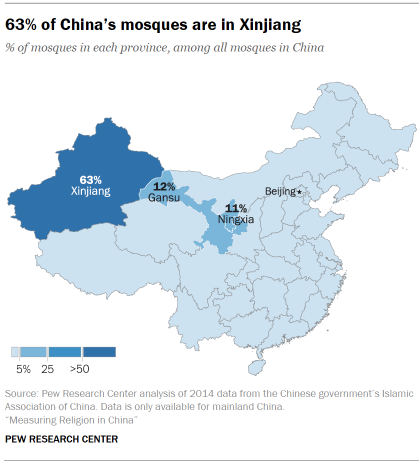

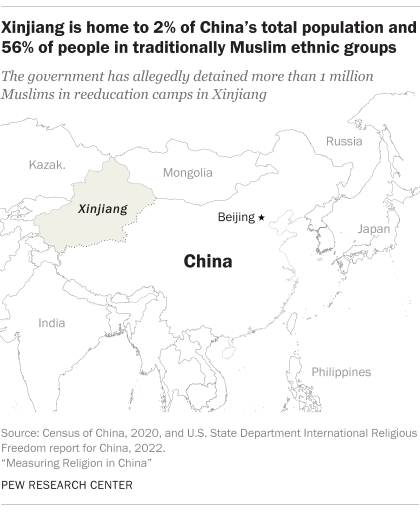

In addition, some zongjiao groups, particularly Muslims, face harsh treatment. The U.S. government estimates that Chinese authorities have detained more than 1 million Chinese Muslims, primarily Uyghurs, in “specially built internment camps.” The U.S. State Department has described abuses against Muslims in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region as crimes against humanity and genocide. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has said the detention of predominantly Muslim groups and deprivation of their fundamental rights “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity,” though the UN report avoids the controversial term “genocide.” For its part, the Chinese government has denied all allegations of genocide, torture, forced organ harvesting and sterilizations involving Muslims. Chinese authorities describe their treatment of Muslims as education and counter-terrorism efforts.

Christian groups also have accused China of religious persecution. For example, the government has arrested “underground” Catholic bishops and priests who are not affiliated with the official Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, as well as Protestants who attend unauthorized places of worship also known as “house churches” (jiating jiaohui 家庭教会). Some Christians reportedly have been held in internment camps.

Because of these policies toward Muslims, Christians and other religious groups, China consistently ranks among the countries with the highest levels of government restrictions on religion, according to Pew Research Center’s annual reports on the topic.

For all the linguistic, cultural and political reasons described above, many Chinese people may be reluctant to associate themselves with religion (zongjiao) or to consider themselves to have a religious belief (zongjiao xinyang). Some zongjiao adherents may choose not to reveal this identity in surveys. (For more discussion of this issue, read “Can Chinese survey data be trusted?”)

Because of political sensitivity, studying religion in China also can be a minefield for scholars.

Challenges facing scholars of religion in China

Scholarly interest in the scientific study of religion in contemporary China seemed to be rising at the beginning of this century. In 2004, Purdue University sociologist Fenggang Yang organized the first annual Conference of the Social Scientific Study of Religion in China and a related training program. The conference was held each year until 2020. Hundreds of Chinese scholars attended for training on social scientific approaches to religion, opportunities to present research, and publishing advice. Training programs emerged in the United States for scholars from China and non-Chinese scholars studying religion in China, especially at the Center on Religion and Chinese Society at Purdue University, which later evolved into the Center on Religion and the Global East. New journals and edited volumes emerged to publish the results of this scholarly activity.

However, in recent years, studying modern religion in China has become more problematic. While some scholars continue to research the current state of religion in China, others have abandoned the field due to Chinese government policies that discourage the study of sensitive topics. Scholars who continue to focus on religion do so with increased caution about the scope of their research and how they present their findings. Such trepidation is not limited to scholars living in China, nor is it exclusive to those studying religion. A 2018 survey of more than 500 scholars outside mainland China who study Chinese society, conducted by political scientists at the University of Missouri and Princeton University, found that the Chinese government monitors research activity and sometimes retaliates against researchers.

About 9% of the survey’s respondents said they had been “invited to tea” to discuss their research with Chinese authorities. Access to archives was denied to roughly a quarter of those who asked for it. In addition, 5% reported difficulties getting travel visas, and about 2% were formally banned from visiting China. Scholars researching Xinjiang and Muslims were among those most likely to report visa complications and interviews with authorities.

In their analysis of this survey data, researchers Sheena Chestnut Greitens and Rory Truex conclude that the Chinese government creates ambiguity to intimidate scholars. Two-thirds of respondents said their research was sensitive, and some changed a project’s focus or abandoned a project altogether because of its sensitivity. However, most did not report any direct intervention from a government official. Respondents were slightly more likely to say that a government official had issued a warning to them through a colleague than to say an official had approached them directly.

Another factor limiting knowledge about the state of religion in China is restrictions on survey research and ambiguity about what may be permissible in surveys. In recent years, it has become increasingly difficult and, in some cases, impossible for foreign organizations to partner with Chinese institutions to conduct surveys in China. Furthermore, the staff of Chinese survey organizations may be uncertain which religion questions will elicit pushback from the government, and they may be highly cautious when considering whether to include religion measures in surveys of general attitudes and behaviors.

To our knowledge, the only surveys still collecting national data on religion in China are academic surveys, such as the Chinese General Social Survey and the China Family Panel Studies, which are supported directly or indirectly by Chinese government funding. For many years, Pew Research Center has been interested in collaborating on a survey of religion and spirituality in China. However, after investigating the possibility of doing so with various partners in China, we concluded that, given government restrictions, we could not carry out a survey dedicated to religion at this time.

Cultural traditions with spiritual underpinnings

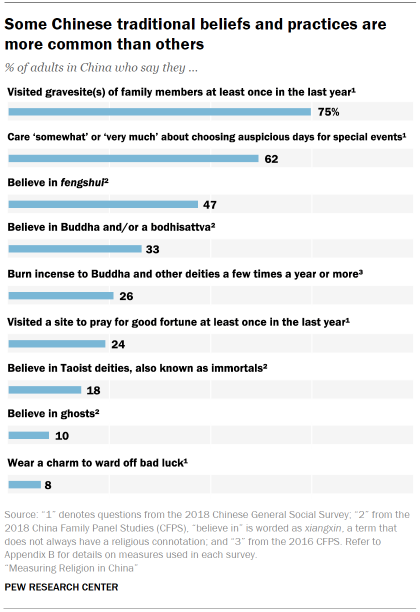

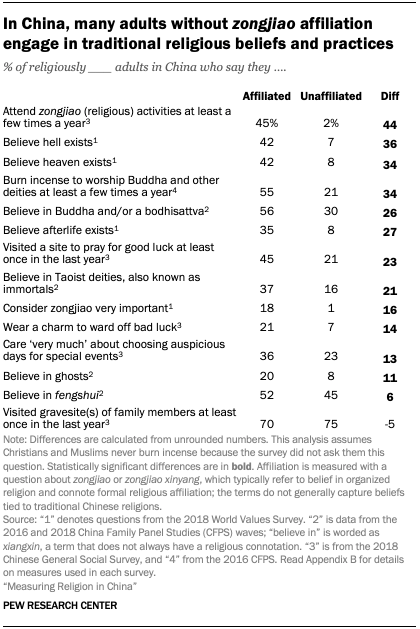

In addition to the formal zongjiao measures and explicitly spiritual ones (belief in Buddha, burning incense) previously discussed, this report also analyzes several widely practiced rituals and customs that are considered cultural but may have religious or spiritual dimensions.

These traditions are observed by many Chinese people with and without a zongjiao affiliation. Chinese surveys have not asked respondents whether they perceive spiritual significance in these beliefs and practices, and the available data does not tie these activities to specific religions.

Gravesite visits

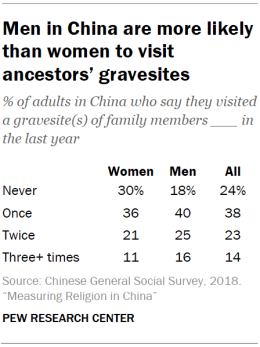

Three-quarters of Chinese adults visited a family member’s gravesite at least once in the last year, according to the 2018 CGSS. Visiting gravesites, especially on the Qingming Festival (Qingming Jie 清明节), or Tomb Sweeping Day, is part of the Confucian tradition of ancestor veneration (jizu 祭祖 or jisi zuxian 祭祀祖先). It commonly involves rituals with religious underpinnings, such as burning incense and “spirit money” or joss paper, making offerings of food and drink, and making wishes to ancestors.5

However, not all Chinese people engage in these rituals when visiting gravesites. For instance, some Chinese Christians may observe Tomb Sweeping Day to honor their parents or loved ones, yet intentionally distance themselves from ancestor worship by refraining from making wishes, burning “spirit money” or leaving offerings.

Fengshui

Nearly half of Chinese adults (47%) believe in fengshui (风水), according to the 2018 CFPS. Fengshui is a traditional Chinese practice of arranging objects and physical space to promote harmony between humans and the environment. Although people who practice fengshui may not think of it as a religious concept, it has roots in Taoism and sometimes involves belief in divine intervention.

Related practices include selecting auspicious days for important occasions and consulting fengshui masters to ward off bad luck.

Auspicious days

Six-in-ten Chinese adults (62%) say they care either “somewhat” or “very much” whether special occasions take place on an auspicious day or an inauspicious day, according to the 2018 CGSS. Choosing an auspicious day usually involves consulting the Chinese almanac or a fengshui expert. About a quarter of adults (24%) say they care very much about selecting auspicious days for special occasions, which can include weddings, funerals or moving to a new home.

Good fortune

Other traditional customs are less common. For instance, 24% of Chinese adults say they visited a site – typically a temple or shrine – to pray for wealth or good fortune in school, business or other matters in the past year, according to the 2018 CGSS. This includes 10% who did so twice or more in the past year. And 8% of Chinese adults say they carry a lucky charm or amulet to bring them good fortune or keep them safe from harm.

Mixing of beliefs

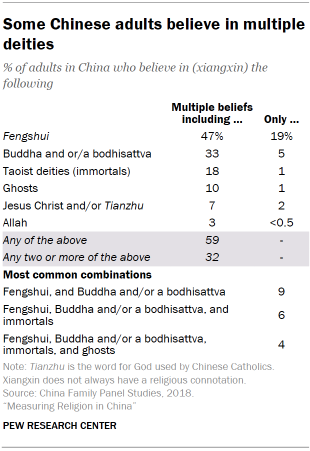

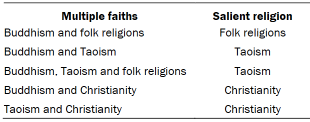

Many Chinese people engage in beliefs and rituals from multiple religious traditions. Chinese surveys do not ask respondents to state how often they do this, but a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) indicates that combinations are quite common.

For example, about 40% of Chinese adults say they believe in at least one of the following: Buddha and/or a bodhisattva; Taoist deities; ghosts; and other gods or religious figures, such as Jesus Christ and Allah. And 20% believe in more than one of these religious concepts or deities. When fengshui (风水), a practice with Taoist underpinnings, is included, the share of Chinese adults who believe in both fengshui and at least one of these other ideas reaches 28%. The CFPS survey asks respondents whether they believe in each of the deities and religious concepts in a list. The Chinese term for “belief” (xiangxin 相信) used in this question does not necessarily connote religious faith. Refer to the Key terms section for more detail.

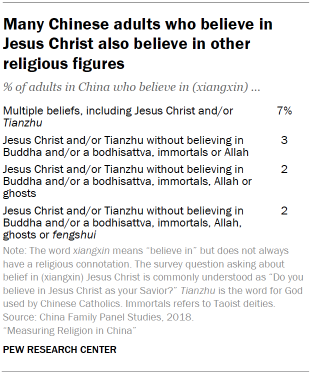

Some Chinese people who believe in figures associated with monotheistic religions, such as Allah and Jesus, also believe in traditional Chinese deities or supernatural forces. For example, about 7% of Chinese adults say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (天主), a word used by Chinese Catholics for God. But only 2% hold such beliefs while rejecting all other deities and supernatural forces.

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center analysis of data on religion in China, part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which seeks to understand global religious change and its impact on societies.

The remainder of this report includes:

- A chapter on signs of religious change in China

- Chapters on the major religious groups in China: Confucianism, Taoism and Chinese folk religions, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, non-religion

- A brief history of Chinese government policy toward religion

1. Religious change in China

It is unclear whether there has been any significant change since 2010 in the percentage of Chinese adults who identify with a religion or engage in religious beliefs or practices.

Some scholars have relied on a mix of fieldwork studies, claims by religious organizations, journalists’ observations and government statistics to suggest that China is experiencing a surge of religion and is perhaps even on a path to having a Christian majority by 2050.

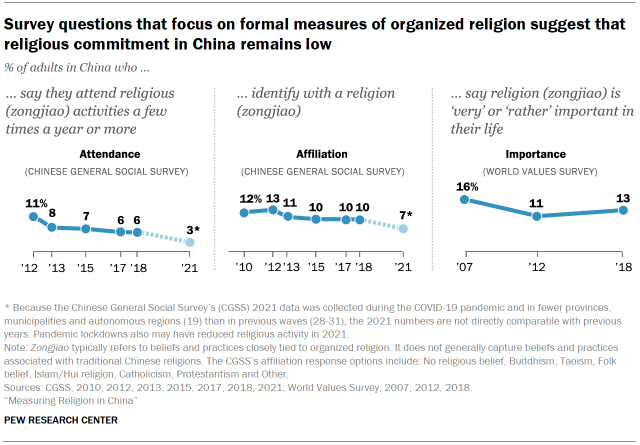

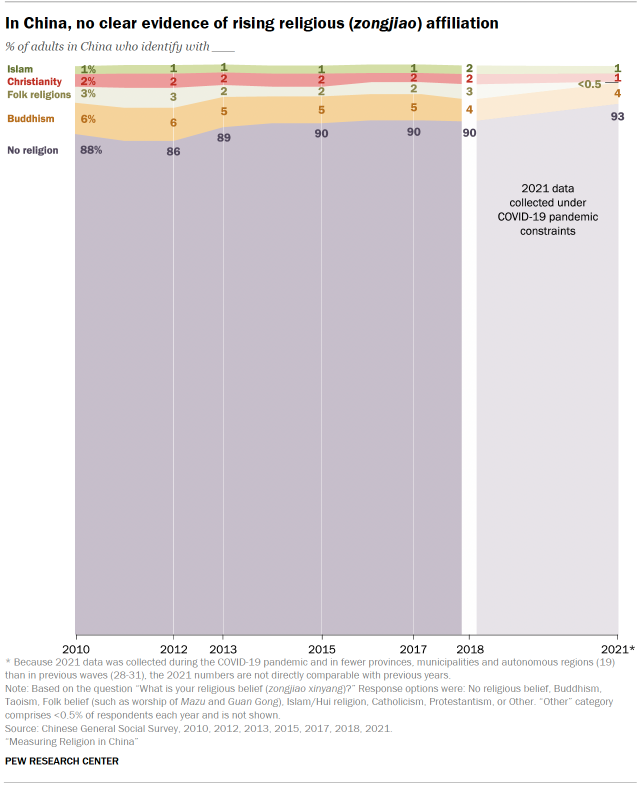

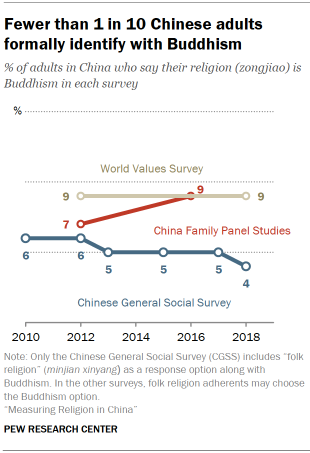

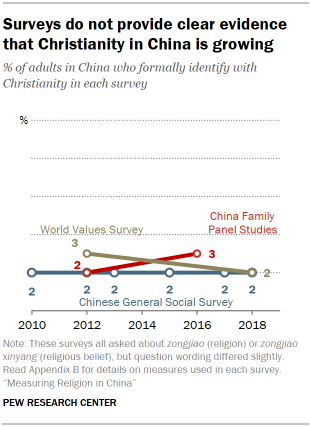

However, more than a decade’s worth of data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), the World Values Survey (WVS) and other large-scale surveys provides no clear confirmation of rising levels of religious identity in China, at least not as embodied by formal zongjiao (宗教) affiliation and worship attendance.

Changes in traditional beliefs and practices beyond zongjiao are difficult to quantify, due to a lack of comparable measures over time. Although several Chinese surveys have included questions about traditional beliefs and practices at least once, their wording and/or methodology have changed from wave to wave. As a result, these surveys cannot reliably measure change over time in traditional beliefs and practices.

In short, this report finds no empirical survey evidence that China has experienced a surge in religion since 2010 – but also cannot firmly rule it out, given the many sources of uncertainty.

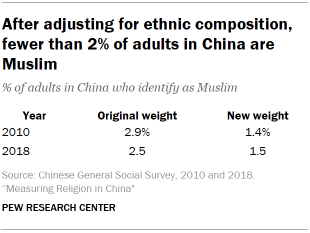

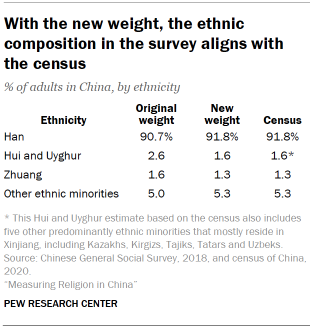

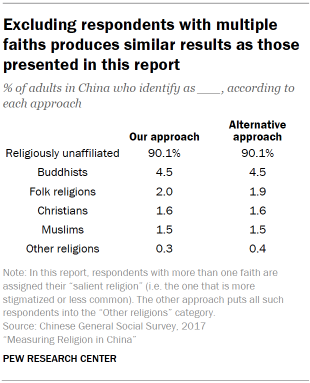

Zongjiao measures

Overall, survey measures on zongjiao identity and practice, which capture a narrow and relatively formal range of religious engagement, have generally been stable since 2010, and in some cases seem to have decreased. According to the CGSS, 12% of Chinese adults claimed a religious affiliation (zongjiao xinyang 宗教信仰) in 2010. While this may seem slightly higher than the 10% who claimed a religious affiliation in 2018, the difference is within the margin of sampling error and is not statistically significant.

More recently, the 2021 CGSS found 7% of respondents identified with any religion. However, the 2021 wave covered fewer provinces and therefore may not be directly comparable with earlier waves.6

The CGSS does not show a significant increase in the shares of self-identified Catholics, Muslims, Protestants or Taoists during this period, and it indicates that the share of Chinese adults who formally identify with Buddhism dropped slightly.7

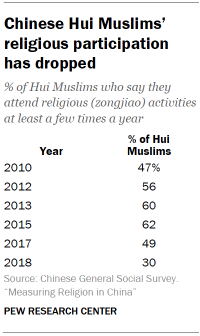

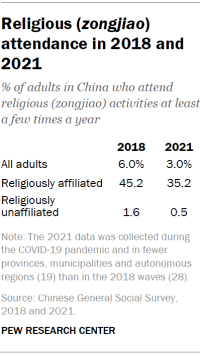

Meanwhile, fewer Chinese adults reported attending religious (zongjiao) activities. In 2012, 11% of respondents said they attended religious activities at least a few times a year. By 2018, 6% said they did so, a decline that is statistically significant. In the 2021 CGSS, just 3% of respondents reported attending zongjiao activities – though the 2021 figure may have been affected by a combination of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions and more sporadic sampling in China’s various regions.

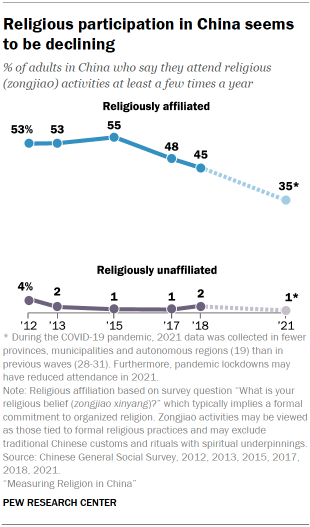

What about the roughly one-in-ten respondents who claim a religious affiliation? Has their level of religious activity increased? The available data suggest the answer is “no.” The share of religiously affiliated Chinese adults who say they attend religious (zongjiao) activities at least a few times a year dropped from 53% in 2012 to 45% in 2018. In 2021, just 35% of religiously affiliated Chinese adults reported attending religious activities at least a few times a year – though, again, 2021 could be an anomalous year because of the pandemic.

Between early 2020, when the coronavirus broke out in Wuhan, China, and the end of 2022, when the Chinese government reopened the country, all places of worship in China experienced temporary or long-term shutdowns as part of the central government’s “zero-COVID” policy.

Initially, in early 2020, all religious sites in China were closed, and gatherings were banned in an effort to contain the virus. Later that year, many sites reopened after the outbreaks in their local areas had subsided, but some sites remained closed. And some that reopened were subsequently shut down again due to fresh outbreaks or rebounding cases of COVID-19.

During the pandemic, some Chinese people engaged remotely in religious activities, such as virtually venerating ancestors on Tomb Sweeping Day (also known as the Qingming Festival) and attending Taoist services online. But it is unclear how virtual participation in zongjiao activities may have affected the way respondents answered the zongjiao attendance question in the 2021 CGSS.

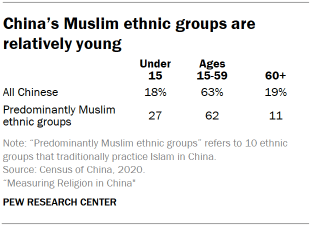

Differences by age

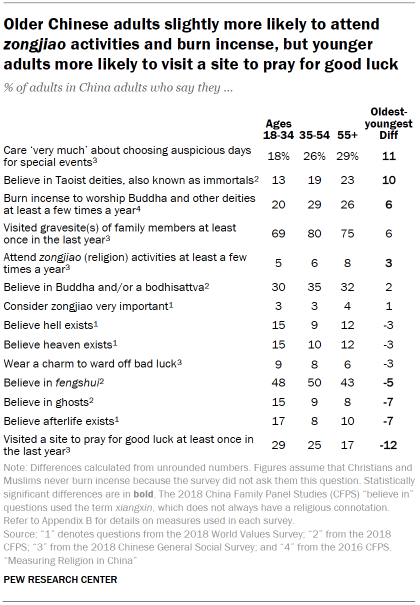

An analysis of age patterns in the 2018 CGSS paints a mixed picture. For example, young adults are slightly less likely than older Chinese people to say they attend zongjiao activities. About 5% of Chinese adults under 35 in 2018 said they attend zongjiao activities a few times a year or more, compared with 8% of those ages 55 and above.

Surveys also indicate that younger adults are less likely than those ages 55 and older to care “very much” about choosing auspicious days for special occasions (18% vs. 29%), according to the 2018 CGSS. And younger adults are less likely to burn incense to worship Buddha and other deities, according to the 2016 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) survey.

However, some folk religious beliefs and practices are more common among young Chinese adults than among their elders.

For example, 29% of adults under 35 reported in the 2018 CGSS that they had visited a place – typically a shrine or temple – to pray for good fortune in school, health or business in the past year, compared with 17% of those ages 55 and older. Adults under 35 also are somewhat more likely than older Chinese to believe in ghosts and in fengshui (风水), the 2018 CFPS finds.

There is no clear pattern by age group on several other measures, such as belief in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva or belief in heaven or hell.

(For more on how Chinese survey respondents may interpret these questions, read the discussion of Chinese religious traditions in Chapter 2.)

Official numbers of worship sites and personnel

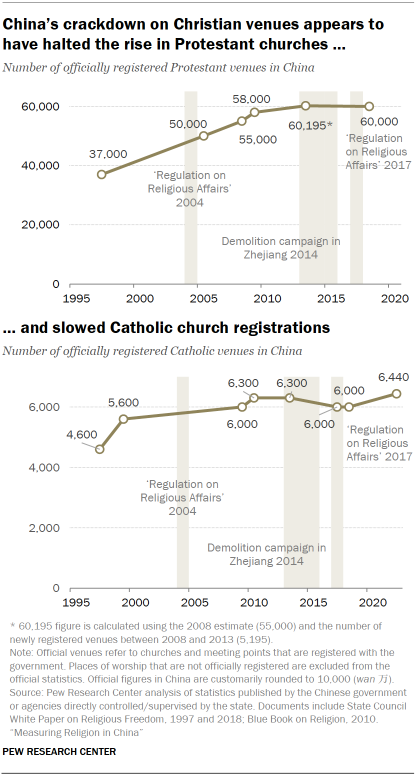

Government figures on places of worship, as well as data on tourism at religious heritage sites, generally rose for traditional Chinese religions between 2009 and 2018. By contrast, the numbers of officially registered Protestant and Catholic churches and Islamic mosques remained virtually unchanged.

Meanwhile, the numbers of officially registered religious personnel have followed different trajectories, with some religious groups (such as Buddhist monks and nuns) experiencing increases and others (such as Taoist clergy) facing declines.

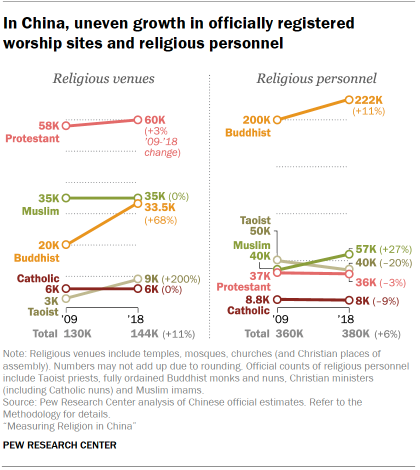

According to China’s State Council Information Office (SCIO), the total number of religious sites registered with the five official religious associations increased by 11%, from about 130,000 in 2009 to 144,000 in 2018, largely due to a surge in Buddhist and Taoist temples. The overall increase in worship sites outpaced Chinese population growth of around 6% during that time.

The SCIO does not track folk religion venues, as there is no supervisory religious association for folk belief. But data from several Chinese provinces that publish regional counts of folk religion temples indicates that these far outnumber the total number of registered worship sites.8 (For more about worship sites tied to traditional Chinese religions, read “How many Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian and folk religious sites are there in China?”)

While the SCIO’s count of religious venues is the most comprehensive dataset available, it has limitations: The figures do not include unregistered or unauthorized sites, and some authorized religious sites also appear to be missing. One possible explanation for this inconsistency is that the Chinese words for “register” – dengji (登记) or zhuce (注册) – are ambiguous. They can mean either “put on local government record” or “granted formal registration.” When local authorities report that they have “registered” a site, it is not always clear which of those two events has occurred.

Because local authorities across China have intensified their efforts since 2017 to absorb unauthorized places of worship into the official system (banning unauthorized churches that refuse to join the state-controlled associations), one might have expected to see an increase in the number of authorized Christian worship sites in recent years.9

However, government figures show no growth in the numbers of formally registered Protestant and Catholic sites between 2009 and 2018, the latest year for which official figures are available.

The next section presents government data on Taoist and Buddhist religious sites and personnel. Parallel discussions for other religions can be found in the Christianity chapter and the folk religion section.

Taoist and Buddhist worship sites and clergy

The number of officially registered Taoist temples tripled from 3,000 in 2009 to 9,000 in 2018, according to the SCIO.10 The number of officially registered Buddhist temples rose by about 68% during that time, from 20,000 to 33,500.

There is some evidence that most or all of this growth took place in the early part of that period.11 In 2012, the director of the National Religious Affairs Administration (formerly the State Administration for Religious Affairs), Wang Zuoan, shared numbers of Buddhist and Taoist temples that were identical to those released by SCIO in 2018, and the same figures were published again by People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper.12

The increase in the number of registered temples associated with traditional Chinese religions was due, at least in part, to preferential government treatment. In the early 2010s, state and local authorities – eager to boost their local economies and cultural pride by promoting religious tourism – often permitted and even encouraged the construction or renovation of Buddhist, Taoist and folk religion temples.

By 2012, religious venues – which are mostly Buddhist and Taoist – reportedly accounted for nearly half the country’s top-rated (or 5A-rated) tourist sites.13

However, the surge in temple construction and registrations did not last, as the government in 2012 started to crack down on developers who built temples or erected Buddha statues to earn profits from religious tourism. Following guidelines to combat what authorities described as “the commercialization of Buddhism and Taoism,” local authorities began tearing down large, outdoor Buddha statues in unauthorized temples and terminating the construction of unregistered temples. In 2017, the state intensified these efforts, banning any commercially oriented temple construction altogether.

In addition, the number of Taoist and Buddhist clergy did not keep pace with the increase in temples between 2009 and 2018. Taoist clergy dropped by about 20% during this time to 40,000, while Buddhist clergy rose by around 11% to 222,000, according to the SCIO. (Taoist clergy include Taoist priests as well as monks and nuns who have gone through the ritual of ordination; Buddhist clergy refer only to fully ordained monks and nuns.)

These different trajectories may have multiple causes, including that new temples meant to serve tourists may require fewer religious personnel. Meanwhile, as China’s economy has expanded and more people move to cities, monastic life seems to be gradually losing appeal. Even at-home Taoist priests (huoju daoshi 火居道士) may find it difficult to continue the tradition of passing down clergy positions from generation to generation.

In addition, the government’s ban on religious education for children and a law requiring all children to attend schools for a minimum of nine years have added extra challenges for religious groups that largely rely on monastic education to train monks and nuns.

Religious tourism

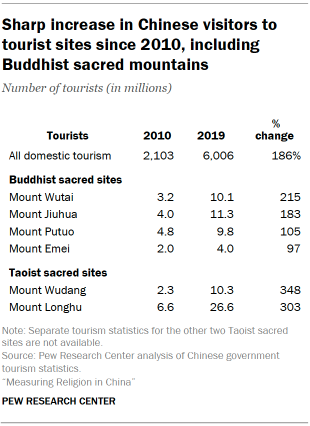

Government data indicates that tourist destinations featuring religion, such as Mount Jiuhua, a Buddhist sacred site, and Mount Wudang, a Taoist holy place with around 200 temples, experienced large increases in visitors between 2010 and 2019.

These gains correspond with an overall boom in domestic tourism in China. In the decade before the coronavirus outbreak, the annual number of domestic tourist visits nearly tripled, from 2.1 billion in 2010 to 6.0 billion in 2019, according to China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

While visitors who travel to religious sites are not necessarily pilgrims, many engage in religious activities at temples and shrines, such as praying for good fortune.14 A study of tourists to Hanshan Temple found that fewer than one-in-six said they visited just for sightseeing, while about half said they had multiple reasons for the trip, including sightseeing, praying for good fortune and engaging with Buddhist history.

A different survey, conducted in 2014, found that about 17% of visitors to Mount Wudang described their trip as a pilgrimage, although fewer than 3% identified as Taoist.

2. Confucianism, Taoism and Chinese folk religions

People burn incense to the god of wealth at Guiyuan Temple in Wuhan, China, in 2017. (Visual China Group via Getty Images)

Confucianism

Named after the sage Confucius (b. 551 B.C.E.), Confucianism is one of the most important philosophical traditions in China. Although it’s widely considered a spiritual philosophy, some scholars classify it as a religion. Its beliefs center on a pervasive, invisible divine power – tian (天), usually translated as “heaven” – that controls humans’ fate and destiny. Confucian teachings focus on filial piety (xiao 孝), loyalty (zhong 忠) and benevolence (ren 仁).

Taoism (religious)

Founded by Zhang Daoling, religious Taoism (Daojiao 道教) dates to the second century C.E. The principal teachings of religious Taoism – similar to philosophical Taoism – focus on nonaction and harmony with the Tao, or universal order. Traditional practices include meditation; self-discipline in diet, exercise and sex; and rituals to promote harmony with the heavenly order or higher forces of the cosmos.

Chinese folk religions

Also called folk belief or minjian xinyang (民间信仰), Chinese folk religions were recorded as early as the Shang dynasty (c.1600-1046 B.C.E), well before Confucianism and Taoism. Folk religions originated in shamanism, and today include a broad range of beliefs and practices directed at supernatural forces — such as fortune telling and making wishes to ancestors and gods. Folk deities include the goddess of the sea (Mazu 妈祖) and the god of wealth (caishen 财神).

Relatively few Chinese adults formally identify with religious and philosophical traditions that originated in China – in large part because, unlike Abrahamic religions, these traditions do not emphasize membership. Moreover, Chinese people generally do not refer to these traditions as religion (zongjiao 宗教).

But Confucianism, Taoism and folk religions nevertheless have a role in the lives of many Chinese people. While a tiny share of Chinese adults describe themselves as believing in (xinyang 信仰) Taoism (Daojiao 道教), Confucianism (Rujiao 儒教 or Rujia sixiang 儒家思想) or folk religions (minjian xinyang 民间信仰), far more say they hold beliefs or engage in practices tied to these traditions.

And even though the Chinese government does not consider Confucianism to be a religion, some of its characteristics are within scholars’ conception of religion. For instance, the Confucian ritual of ancestor worship (jizu 祭祖) – an expression of filial piety (xiao 孝) toward deceased family members – often entails a belief in ancestral spirits and their supernatural power to intervene in earthly affairs.

Buddhism, which is considered a “traditional Chinese” religion even though it originated in India, has strong links to these other belief systems. (Read Chapter 3 on Buddhism.)

Confucianism, Taoism, folk religions and Buddhism are often deeply intertwined, and the differences among them can be indistinguishable to Chinese people. For example, Confucian teachings on ancestor veneration permeate China’s spiritual traditions, such as in the Buddhist Ullambana Festival (Yulanpen Jie 盂兰盆节) and Taoist Zhongyuan Festival (Zhongyuan Jie 中元节). Both events take place annually in Lunar July, a time when ghosts, including deceased ancestors, are believed to visit the world of the living. And both festivals incorporate filial piety (xiao), as manifested during a ritual in which ancestral spirits are commemorated and “rescued” from their suffering.

Folk beliefs and practices, meanwhile, incorporate Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist concepts and also turn them into distinctly folk religious elements. For instance, the popular folk deity, the goddess of mercy (Guanyin 观音), was originally the Buddhist figure Avalokiteśvara, a bodhisattva of compassion often depicted as genderless or male. In Chinese folk religion, Guanyin is understood as a goddess who answers all prayers, including requests for wealth, health, good fortune and giving birth to a son.

Historically, Confucianism, Taoism and folk religions – along with Buddhism – have helped shape Chinese people’s understanding of the universe. Even today, these traditions are tied to Chinese social norms and the country’s national holidays. Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, which in the past were frequently referred to as the “Three Teachings,” typically garner more support from educated elites and authorities than do folk religions, which historically have been marginalized as “illegitimate” and “unorthodox.”15

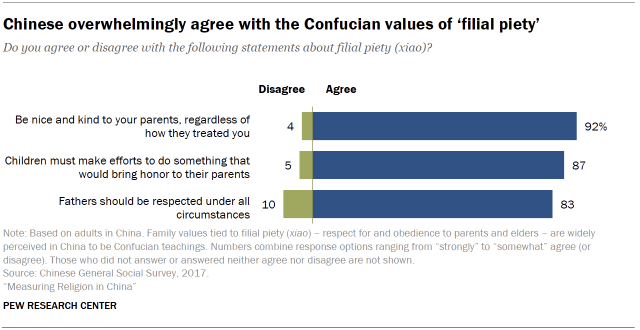

In 2015, the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) included a question about Confucianism and moral values: “Some people say the moral conditions in society are not ideal. If we were to restore moral values in society, what role do you think the Confucian tradition should play?” About two-thirds of respondents said efforts would need to rely at least partly on the Confucian tradition.

Authorities in China often differentiate between traditional beliefs and practices they consider to be “custom,” which are tolerated, versus those that are “superstition” and therefore discouraged or banned. (Some superstitious activities deemed to be “harmless” are allowed.) These distinctions may be blurry and subjective, but they are at least partly rooted in the history of Confucianism, Taoism and folk religion in China.

Festivals and traditions honoring ancestors

The Confucian practice of paying respects to deceased ancestors as if they were living is observed across religious traditions during the month of Lunar July, a time when tradition teaches that the gate of the underworld opens, and ghosts and spirits, including deceased ancestors, are allowed to visit the world of the living.

Folk religion: (Hungry) Ghost Festival (Gui Jie 鬼节)

People make offerings of food and “spirit money” to ghosts and ancestors.

Buddhism: Ullambana Festival (Yulanpen Jie 盂兰盆节)

A festival centered on filial piety and gratitude to all beings. Buddhist monks traditionally perform a ritual called “releasing the flaming mouth” to rescue ghosts, including ancestors, from their suffering.

Taoism: Zhongyuan Festival (Zhongyuan Jie 中元节)

The Taoist deity, Ruler of the Earth, is believed to pardon ghosts of their sins. Taoist priests perform Zhongyuan fasting and offering rituals to rescue ghosts, including ancestors, from their suffering.

Beliefs and practices

Beliefs and practices tied to Confucianism, Taoism and Chinese folk religions generally fall into three broad areas: filial piety (xiao 孝) and ancestor worship (jizu 祭祖), veneration of deities and ghosts, and beliefs that involve supernatural forces, such as fengshui (风水).22

While some of these concepts appear to be distinctly Confucian (ancestor worship), Taoist (belief in Taoist deities), folk religious (caring about auspicious days) or even Buddhist (belief in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva), they defy clear categorization. There is a lot of overlap among these traditions, and Confucianism, Taoism, folk religion (and Buddhism) all are considered to be part of traditional Chinese culture.

In addition, Chinese people often engage in religious beliefs and practices with a range of origins without distinction. Folk religion in particular blends elements from a variety of Chinese traditions, so separating folk beliefs and practices from more “orthodox” belief systems is particularly difficult.

Filial piety and ancestor worship

In its basic form, filial piety (xiao) refers to one’s duties and indebtedness to parents, even after their death. These duties include respect, obedience and care for parents and elderly family members.

In Confucian teachings, ancestor veneration – and the associated ancestral rite (jili 祭礼) described in Confucian texts – is an expression of filial piety. Confucianism’s tenet of filial piety is a pillar of social norms across East Asia and parts of Southeast Asia.

As described in “The Analects,” the ancestor veneration ceremony or rite involves fasting in preparation, wearing ceremonial costumes, and offering elaborate meals to deceased ancestors. One is expected to perform the rites carefully and pay respects to the deceased as if they were living. Confucius was said to insist that venerating ancestors is not a religious act but a form of fulfilling filial responsibilities. Still, the ceremony entails the belief that deceased ancestors continue to exist.

Other Chinese religious traditions have adapted the concept of ancestor veneration in their own way. In Chinese folk religion, for example, failure to venerate one’s ancestors properly brings divine punishment, and the spirits of the dead who were not venerated by their living descendants become “wandering ghosts.”

In China today, ancestor veneration rituals, such as those performed during gravesite visits, are typically steeped in folk religion. Gravesite visits often involve rituals with religious underpinnings, such as burning incense and “spirit money” or joss paper, making offerings of food and drink, and making wishes to ancestors.23

Three-quarters of Chinese adults report that they visited a family member’s gravesite at least once in the last year, according to the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS).

The survey did not ask what rituals people perform at gravesites. Some Chinese people may not engage in any activity that has spiritual or religious underpinnings while caring for an ancestor’s grave. But ethnographic research suggests that Chinese people typically burn incense and “spirit money” when visiting family members’ gravesites.

While most Chinese people venerate ancestors, very few do it as frequently as tradition dictates. Custom calls for paying respects to ancestors at a family gravesite three times a year: on Tomb Sweeping Day, during the Chinese New Year and on the anniversary of an ancestor’s death.

In 2018, only 14% of adults in China said they had visited a family member’s gravesite three times or more in the past year.

Many Chinese people oppose cremations because they are viewed as violating the Confucian understanding of respect for the dead.24 Since 1956, the Chinese government, citing the amount of arable land devoted to burials, has promoted cremation, but the cremation rate has remained far below the government’s target.

Deity worship

In Chinese religious tradition, supernatural beings typically include gods – or deities – and ghosts, i.e., the spirits of the dead. While the spirits of deceased ancestors fall into the category of “ghosts”(gui 鬼), Chinese people rarely use this term to describe their own deceased ancestors.

Gods, which are usually viewed as benevolent and having the power to intervene in worldly affairs, are believed to reside in heaven, Earth or the underworld. They follow a divine hierarchical structure and oversee a jurisdiction in accordance with their position. They may include Buddhist figures, Taoist immortals (shenxian 神仙) and local deities outside of the Buddhist or Taoist pantheons.

Gods can also be the spirits of human heroes. For instance, Lord Guan (Guan Gong 关公) was originally a renowned military general, Guan Yu (160-220 C.E.). He was worshipped by ordinary people as the god of war after his death, and later also by Confucian elites, who extolled Guan Yu as a moral exemplar of loyalty and honesty. Guan Yu was also granted the Buddhist rank of bodhisattva during the Sui dynasty (581-618), and the Taoist title of Emperor Guanduring the reign of Song Emperor Huizong in the 12th century.

Ghosts are often believed to possess the power to intervene in worldly affairs, but they can be malevolent and are of a lower rank than gods. Ghosts are usually confined to the underworld, except during the month of Lunar July, also known as “Ghost Month,” when the gate of the underworld opens and ghosts are allowed to visit the world of the living. It is believed that making food offerings and burning “spirit money” can appease ghosts and prevent them from harming the living.

Belief in deities, including Buddha and/or a bodhisattva and immortals, is more common than belief in ghosts. For example, 18% of Chinese adults express belief in immortals, compared with 10% of adults who believe in ghosts, according to the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS).

Because some gods are venerated across religious traditions, it is not always clear which religion(s) such practices fall into. For instance, burning incense to pay respects to Buddha (shaoxiangbaifo 烧香拜佛) may appear to be a Buddhist practice, but this activity is found across Chinese religious traditions.25 Some people may burn incense to pay respects to Buddha while incorporating distinctly folk religion practices, such as simultaneously making wishes to Buddha.26 Likewise, it is unclear whether a person who says they believe in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva should be considered a Buddhist or a practitioner of folk religion.

Burning incense (shaoxiang 烧香) – usually incense sticks – is believed to open up communication with gods so they can more readily hear people’s wishes. It is an essential component of venerating or paying respects to deities and ancestors, and in Chinese folk religious traditions, burning incense is typically accompanied by making wishes (xuyuan 许愿). Today, the term shaoxiangbaifo is commonly used to describe the act of venerating one or more deities of traditional Chinese religions.

Roughly a quarter of Chinese adults (26%) say they burn incense – at home or in temples – to pay respect to Buddha or deities a few times a year or more, including 11% who do so at least once a month, according to the 2016 CFPS.27 And 24% say they visited a particular destination – typically a temple or shrine – to pray for good fortune in school, business or other matters in the past year, according to the 2018 CGSS.

These measures suggest that most Chinese people are not frequently engaged in traditional religious activities. However, this low level of engagement is consistent with Chinese religious tradition, where people are not expected to pay respects to a god or gods regularly.

Rather, as some scholars have argued, religious engagement in China largely revolves around efficacy (ling 灵or lingyan 灵验) – how well a particular god or ritual responds to a person’s request – and believers are “consumers” who choose from the full array of gods and religious rituals when the need arises.28

Supernatural forces

In Chinese religious tradition, apart from gods and ghosts, supernatural forces, such as fate (ming 命), fortune (yun 运) and fengshui may affect or even largely shape one’s life.29 While ming is predestined and immutable, yun changes. There are a variety of divination practices believed to bring good fortune or ward off bad luck, such as fengshui maneuvering – the practice of arranging objects to create harmony between individuals and their environment – wearing lucky charms, and selecting auspicious days for special occasions.30

Chinese people commonly describe these practices as custom or superstition (mixin 迷信), though they are known to have Taoist underpinnings. It is not always clear whether the practice should be considered religious or which religious tradition it falls under. For instance, some people may consider their fengshui practice to be scientific, while others may hire Taoist priests to perform fengshui activities in a folk religious way, and still others may practice it in a purely Taoist way, as part of Taoist health rituals.

Approximately six-in-ten adults (62%) say they care “somewhat” or “very much” about choosing an auspicious day for special occasions, according to the 2018 CGSS. Almost half (47%) believe in fengshui, according to the 2018 CFPS. And 8% of Chinese adults say they carry a lucky charm or amulet to bring good fortune or keep them safe from harm.

Mixing of beliefs and practices

Traditional Chinese religious or spiritual beliefs and practices are not mutually exclusive. Beliefs in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals and fengshui overlap considerably, and few Chinese hold only one belief. For example, just 5% of adults say they believe in (xiangxin 相信) Buddha exclusively, compared with 9% of adults who say they believe in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva and fengshui at the same time. An additional 6% also believe in Taoist immortals.

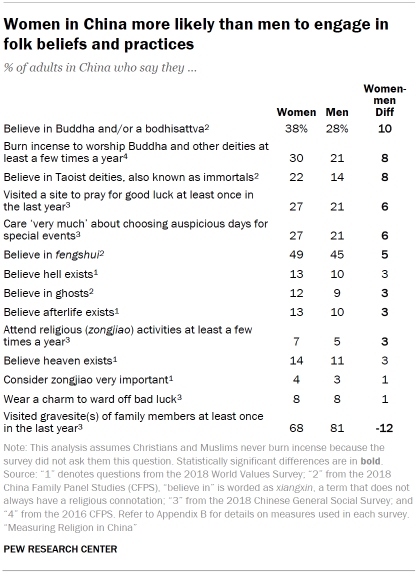

There are significant differences on these belief and practice measures across demographic groups. On average, women, older adults and people with less educational attainment tend to be more engaged in folk religion.

For example, women are consistently more likely than men to say they burn incense to venerate Buddha or other deities. They are also more likely to believe in folk deities, fengshui and auspicious days. However, women are less likely to visit the gravesite(s) of family members, as men are primarily responsible for performing that ritual, according to custom.

Affiliation

The share of Chinese adults who describe their religion (zongjiao) as Confucianism, Taoism or folk religion is much smaller than the share who engage with beliefs and practices from these traditions.

The most common of these identities is folk religion, but still, only about 3% of adults in China identify as adherents of folk religions, according to the 2018 CGSS.31

The CGSS is the only national survey that includes “folk religion” in the religious affiliation question, and it presents worshipping Mazu (妈祖), the goddess of sea, or Guan Gong (关公), commonly venerated as the god of wealth, as examples of folk religion.

The CGSS question may not capture some adults who worship other folk deities, such as the goddess of mercy (Guanyin 观音), earth gods (tudigong 土地公), dragon king (longwang 龙王) or Silkworm Mother (Cangu Nainai 蚕姑奶奶).

Some Chinese people who engage in deity worshipping may not consider themselves religious in the formal sensebecause folk religion is commonly regarded as superstition in China, which the government discourages.

In addition, scholars have noted that practitioners of folk religion sometimes refer to all forms of folk religion as Buddhism and claim Buddhist affiliation, even though they mostly practice folk religion. (Read Chapter 3 for details on Buddhism in China).32

Many people in China do not consider Confucianism to be a religion. This report does not analyze Confucianism as a religious affiliation, and we do not make any estimate of the number of Confucians in China. Taoism is one of the five religions recognized by the government (along with Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam and Protestantism), but very few Chinese adults identify as Taoists in the 2018 CGSS.33

Sidebar: How many Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian and folk religious sites are there in China today?

For various reasons, it is unclear exactly how many traditional Chinese worship sites (temples and shrines with Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian or folk religious elements) there are across China today. Nor is it clear which sites are most common. This sidebar describes the government’s official statistics as well as some unofficial estimates based on surveys of “neighborhood committees,” explaining why neither set of numbers is wholly reliable.

Official data

Chinese government statistics show a total of 43,000 temples – about 34,000 Buddhist sites and 9,000 Taoist sites – across the country as of 2018. However, this count covers only officially registered Buddhist and Taoist venues, which typically include a monastery or housing for monks or nuns, as well as a prayer hall that is open to the public for worship.

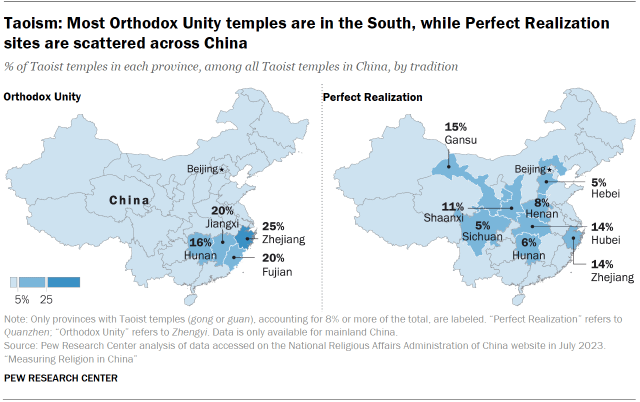

Buddhist temples (si 寺 or siyuan 寺院) included in the official statistics are categorized based on their school: Han, Tibetan or Theravada. (Refer to the Buddhism chapter for more details.) Taoist temples (gong 宫 or guan 观) are usually classified as belonging either to the Perfect Realization tradition (Quanzhen 全真) or to the Orthodox Unity tradition (Zhengyi 正一).34 According to the official figures, somewhat more Taoist temples belong to Orthodox Unity (4,338) than to Perfect Realization (4,011).35 Also, the Perfect Realization tradition has a stronger presence in northern China, while Orthodox Unity tends be more widespread in southern regions, according to data from the National Religious Affairs Administration of China.

Buddhist or Taoist sites without formal registration are excluded from the official statistics. It is possible that the number of unregistered Buddhist and Taoist sites far exceeds those registered, given the high bar for registration, such as having steady income and qualified clergy. In addition, the managers of many sites may have little incentive to register, because local authorities often permit unregistered Buddhist or Taoist venues to operate without much difficulty.36

Meanwhile, folk religion sites – which are mostly shrines and temples– are not tracked closely by the government since folk religion is not one of China’s five official religions and does not have its own supervisory agency.

In 2015, the Chinese government issued, for the first time, a national document urging local governments to regulate folk religion and its sites. However, registration requirements for folk religion sites vary widely by province. For instance, in Guangdong province, any folk religion site seeking to register must have a minimum building area of 500 square meters (5,382 square feet), while in Hunan province, the requirement is just 50 square meters. These inconsistencies add to the challenge of estimating the number of folk religious sites across China.

Although Confucianism is not officially recognized by the government as a religion, there is a national association that tracks Confucian temples (wenmiao 文庙 or kongmiao 孔庙). Traditionally, these were sacred places reserved for educated elites to worship Confucius. Today, they are open to all visitors. Government statistics show 1,600 Confucian temples across China. However, this count does not include ancestral halls or temples (zongci 宗祠 or citang 祠堂) – places of worship dedicated to ancestors of the same family lineage, which are closely tied to Confucianism.

Estimating numbers of worship sites from surveys of local jurisdictions

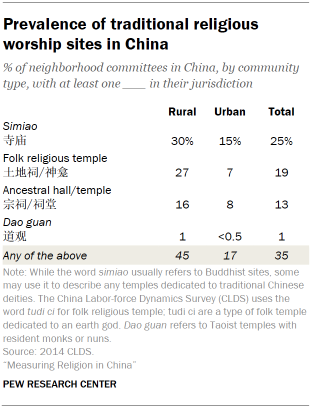

Survey data provides an alternative way to estimate the prevalence of traditional religious sites. The 2014 China Labor-force Dynamics Survey (CLDS) of neighborhood committees – the smallest administrative unit in China – indicates that 35% of such committees have in their jurisdiction at least one temple or shrine associated with traditional Chinese religions, such as a temple with a Buddhist connection (simiao 寺庙), a Taoist temple that includes a monastery (dao guan 道观), an ancestral hall (zongci or citang), or a folk temple dedicated to an earth god (tudi ci 土地祠) or shrine dedicated to other local deities (shenkan 神龛).

All told, the CLDS data suggests there may have been as many as 280,000 traditional worship sites in China in 2014.37 However, that figure also may be low. Although the survey asked about the presence of temples without specifying their registration status, it is possible that neighborhood committees reported only temples that had received some type of government approval, such as formal registration or at least tacit consent from local officials.

Ancestral halls

The CLDS report on neighborhood committees shows that about 13% of such committees have in their jurisdiction at least one ancestral hall (zongci or citang). Neighborhood committees in rural areas, known as “villagers’ committees,” are particularly likely to have at least one site dedicated to ancestors (16%). A neighborhood committee generally represents between 1,000 and 3,000 households, while a villagers’ committee is comprised of an average of around 370 households.38

These numbers suggest there are more than 102,000 ancestral halls in China. But this may be a conservative estimate, because 7% of neighborhood committees report having two or more ancestral temples in the survey.

Buddhism

CLDS data indicates there were more than 190,000 Buddhist temples (simiao) in China, far greater than the government’s count of 34,000 officially registered Buddhist sites. However, that 190,000 figure could overstate the number of Buddhist venues with a monastery, because the term “simiao”is also sometimes used to describe any temple or shrine that houses Buddhist deities along with various other traditional Chinese religious deities.

Taoism

As for Taoist temples, CLDS data indicates that only 1% of neighborhood committees have at least one such temple in their jurisdiction. However, this count is based on a survey question asking about dao guan, which are temples with resident Taoist monks or nuns. It does not account for worship sites with some looser Taoist connection, such as temples or shrines that house Taoist deities along with various other traditional Chinese religious deities.

Folk religion

Folk religious temples, measured by the presence of temples (tudi ci) or local shrines (shenkan), seem to be relatively common in China, being present in 19% of neighborhood committees, according to the 2014 CLDS. Neighborhood committees in rural areas are particularly likely to have a site dedicated to local folk deities (27%). However, not all folk religious sites are dedicated solely to local folk deities, national heroes, trade gods, and/or other so-called “tutelage” or protector gods (such as the mountain god). In fact, it is common for folk religious temples also to house Buddhist or Taoist figures.

As a result, the CLDS-based estimate that there are at least 165,000 folk temples (tudi ci) or local shrines (shenkan) might not count some sites that house Buddhist or Taoist deities together with folk deities, thus leading to a possible undercount of folk religious sites in China.

Furthermore, while the CLDS data may seem to suggest that Buddhist temples are the most common variety in China, this conclusion may not be warranted, due to the complex interconnections of Buddhism, Taoism and folk religion. Some temples or shrines may not fall neatly under one religious category, because they house multiple Buddhist, Taoist and folk deities at the same time.

There is some evidence suggesting the number of temples that fall outside of official statistics declined in the past decade when local authorities tightened controls over folk religion. For example, in Zhejiang, 35,000 folk religious sites were listed in 2013, but that number dropped by half to 17,000 in 2020 as sites that failed to meet the government’s registration requirement were demolished, closed or converted into secular facilities.

3. Buddhism

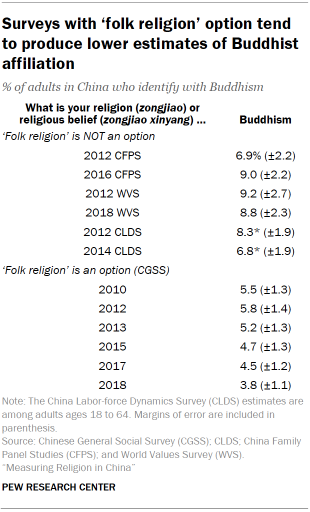

Buddhism (Fojiao 佛教) is the largest officially recognized religion in China. The share of Buddhists in China ranges from 4% to 33%, depending on the measure used and whether it is based on surveys that ask about formal affiliation with Buddhism or beliefs and practices associated with Buddhism.

The share of Chinese adults who formally identify (zongjiao xinyang 宗教信仰) with Buddhism is about 4%, representing about 42 million adults, according to the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS).39

But 33% of Chinese adults, representing about 362 million adults, believe in (xiangxin 相信) Buddha (fo 佛) and/or a bodhisattva (pusa 菩萨), according to the 2018 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) survey – though this number also includes many people who believe in other religious figures as well, such as Jesus Christ or Taoist immortals.40

Buddhism in China has three main branches. Han Buddhism, or Chinese Buddhism, accounts for the vast majority of the country’s Buddhists, as measured by the number of registered temples. (Refer to “Geographic distribution of Buddhist temples” for more detail.)

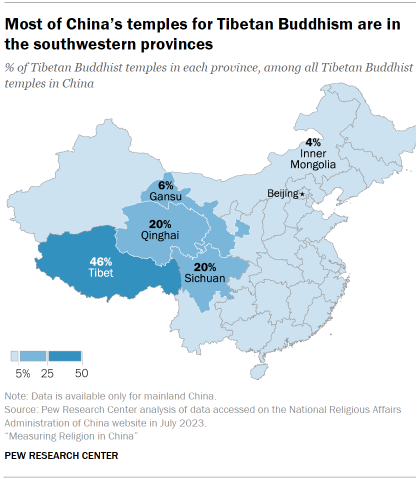

Tibetan Buddhism and Theravada Buddhism are practiced primarily by ethnic minorities in the Tibetan Plateau, Inner Mongolia and along the southern borders with Myanmar, also called Burma, and Laos. In China, the word “Buddhism” typically refers to Han Buddhism.

Although Buddhism originated in India, Han Buddhism has developed distinctly Chinese characteristics while also influencing older Chinese belief systems. Han Buddhists generally espouse the Confucian ideal of filial piety (xiao 孝) and have adopted practices that align with ancestor worship, such as praying for the well-being of deceased ancestors.45 They also have incorporated the Taoist practice of breathing exercises.

In the past decade, government policies have been relatively lenient toward Han Buddhism. President Xi Jinping has extolled (Han) Buddhism as one of the essential forms of Chinese traditional faith with a role to play in restoring morality, and has commended it for having “integrated … with the indigenous Confucianism and Taoism.”

How many Buddhists are there in China?

As with Taoism and folk religion in China, assessing the size of the Buddhist population is challenging due to Buddhism’s blurry boundaries with other traditional Chinese religions. Unlike Christianity and Islam, Buddhism does not require exclusivity of belief or practice. Buddhists do not need to affiliate with a local temple or Buddhist association, nor must they participate in the formal ritual of “taking refuge” (guiyi 皈依) to identify with Buddhism.

As a result, survey questions that measure Buddhist self-identification (i.e., “What is your religious belief?” “Which religion do you believe in?” and “To which religion do you belong?”) fail to capture adults who engage in Buddhist beliefs and/or practices but do not consider themselves formally affiliated with Buddhism. Survey questions that ask about Buddhist affiliation tend to produce much lower estimates than those that ask about belief in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, or about the burning of incense to pay respects to Buddha and other deities (shaoxiangbaifo 烧香拜佛).

That said, belief and practice measures are not a wholly accurate proxy for Buddhist identity, either. Because of Buddhism’s embeddedness in Chinese folk religion, seemingly Buddhist measures are not exclusively Buddhist, and may also capture folk religion practitioners. For instance, the Buddhist figure of Avalokiteśvara, a bodhisattva often depicted as genderless or male, has evolved into an important folk deity, the goddess of mercy (Guanyin 观音), which makes it unclear whether a person worshipping a bodhisattva is a Buddhist or a practitioner of folk religion. (Refer to Chapter 2 for a discussion of how Buddhism intertwines with other Chinese religious traditions.)

Meanwhile, Chinese people sometimes do not distinguish between certain concepts in folk religion and Buddhism. In southern Fujian, for example, people commonly refer to all types of folk religion as Buddhism (Fojiao 佛教).46 In other words, some people who primarily practice folk religion may choose “Buddhism” as their religious belief (zongjiao xinyang) in surveys, especially when “folk religion” is not offered as an option. Indeed, surveys that give respondents the option to self-identify with “folk religion” tend to produce lower Buddhist estimates than those that do not offer “folk religion” as an option.

Moreover, there is a varied understanding of what it means to “be Buddhist.” Some Chinese who worship Buddha as one of many folk deities may describe themselves as “believing in Buddha” (xinfo 信佛), while those who are devoted to studying Buddhist scriptures may say they are “studying Buddha” (xuefo 学佛) or refer to themselves as “Buddha’s disciples” (fomen dizi 佛门弟子). Others may believe that only Buddhist monks and nuns should claim Buddhism as their zongjiao (宗教) or zongjiao xinyang.

While it may be possible to approximate the number of Buddhists based on the share of adults who engage in distinctly Buddhist rituals and activities – such as “taking refuge” and chanting Buddhist sutras – there is a shortage of data on these measures. The last publicly available national survey to ask questions about clearly Buddhist rituals and activities was the 2007 Spiritual Life Study of Chinese Residents, which found that only a small fraction of Chinese adults had undergone the formal ritual of conversion (2%), recited Buddhist prayers (1%) or occasionally read Buddhist scriptures (1%).

Even the Buddhist Association of China – the official supervisory agency for Buddhist affairs in China – provides population estimates that it says are based on “incomplete statistics” (bu wanquan tongji 不完全统计). In 2017, it estimated that China had more than 100 million Buddhists, equivalent to more than 9% of the adult population. How this estimate was derived is unclear.

Buddhist beliefs and practices

Belief in Buddha

Fully 33% of Chinese adults say they believe in (xiangxin) Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, according to the 2018 CFPS survey.47 This figure includes those who chose one or more additional deities from among the response options, such as “Taoist immortals,” “Jesus Christ,” “Catholic God” and “Allah.” The share of Chinese adults who say they believe in Buddha and no other deities is 16%.

Burning incense to worship Buddha (and other deities)

About a third of Chinese adults say in the 2016 China Family Panel Studies survey they burn incense to worship Buddha and other deities at least once a year (35%), including 26% who engage in such practice a few times a year or more. Again, questions about Buddha – such as those that measure belief in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva or the burning of incense to worship Buddha and other deities – are not distinctly or exclusively Buddhist. (Refer to discussion in previous section.)

Zongjiao affiliation

In the 2018 CGSS – which includes a “folk religion” option – 4% of Chinese adults said their zongjiao xinyang is Buddhism. Estimates of Buddhist affiliation from surveys that do not offer the folk religion option, such as the CFPS and World Values Survey (WVS), are as high as 9%.48

One advantage of the CGSS, which is the only survey that includes “folk religion” as a response option, is that it may help differentiate Buddhists from folk religion practitioners who might otherwise choose the “Buddhism” response option. Another advantage of the CGSS is that it measures formal affiliation with Buddhism using similar methods across waves, and it produces Buddhist estimates that do not swing dramatically between waves. The CGSS estimate of the Buddhist population is conservative relative to the other sources, and it seems to trend slightly downward over time.

The WVS and CFPS each have only two publicly available datasets with a consistent measure of Buddhist affiliation. They provide less information about change over time than the CGSS.

As discussed earlier, zongjiao-focused questions do not capture the full scope of traditional Chinese religions, including Buddhism. Still, zongjiao affiliation measures provide useful context.49

Not surprisingly, surveys show that adults who claim Buddhism (Fojiao) as their religion (zongjiao) tend to be more actively engaged in zongjiao religious practice than those who believe in (xiangxin) Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, and they are also more likely to consider zongjiao very important in their lives, according to the CFPS.50

Geographic distribution of Buddhist temples

In China, Buddhist temples are known as si (寺) or siyuan (寺院). They often consist of several buildings, including a monument housing a sacred Buddhist relic as well as a monastery or housing for monks or nuns, and a prayer hall that is open to the public for worship.

Simiao (寺庙), which is another term for Buddhist temples, can also refer to any temples or shrines that house Buddhist deities, along with various other traditional Chinese religious deities.

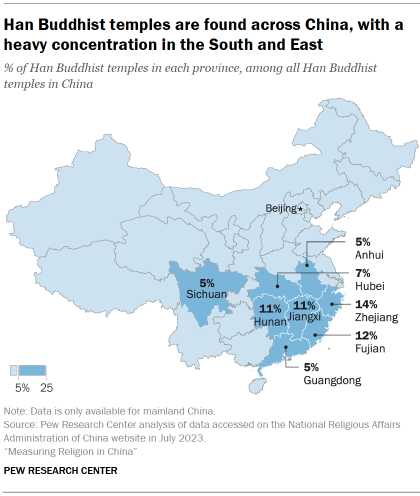

The National Religious Affairs Administration (NRAA), which measures officially registered Buddhist temples with a monastery, found that there are about 34,000 such venues in China.51 Han Buddhist temples are most common (28,528), followed by Tibetan (3,857) and Theravada (1,705) temples.

However, these numbers do not include unregistered Buddhist temples. To be officially registered, religious venues in China must meet specific requirements, including having a steady income and qualified clergy. Some temple managers may have little incentive to register because local authorities often permit unregistered Buddhist temples to operate normally (even though they crack down on unregistered churches.)52

Moreover, official statistics fail to count some folk temples (miao 庙) that also house Buddhist deities along with various other traditional Chinese religious deities.

The 2014 China Labor-force Dynamics Survey (CLDS) of neighborhood committees – the smallest administrative unit in China – which asks neighborhood committee staff about the presence of Buddhist temples (simiao) in their jurisdiction, indicates that temples with some type of Buddhist connection are far more common than NRAA data indicates.

A Pew Research Center analysis of the 2014 CLDS suggests that there are at least 192,000 such temples (simiao) dedicated at least partially to Buddhist deities in China, more than five times the officially registered number of Buddhist temples. Officially registered temples usually have resident monks and nuns, which is not necessarily true for unregistered temples. (For more on other types of traditional Chinese worship sites, refer to the “How many Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian and folk religion sites are there in China?” sidebar.)

According to NRAA, Han Buddhist temples are widespread throughout the country, with a heavy concentration in the southeastern provinces of Zhejiang, Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Hubei and Jiangxi. This concentration is likely tied to higher rates of economic development in these areas, which may have helped accelerate temple construction and repairs after the Cultural Revolution.

Tibetan Buddhist temples are largely confined to the southwestern region known as the Tibetan Plateau, which encompasses the Tibet Autonomous Region established by the Chinese government in 1965, as well as portions of the neighboring provinces of Sichuan and Qinghai. (In this report, Tibet refers to the Tibet Autonomous Region.) Nearly 86% of China’s Tibetan Buddhist temples are found in Tibet, Sichuan and Qinghai.

All Theravada Buddhist temples registered with the NRAA are found in the southwestern Yunnan province, particularly in areas heavily populated by Dai people, such as Xishuangbanna prefecture.

4. Christianity

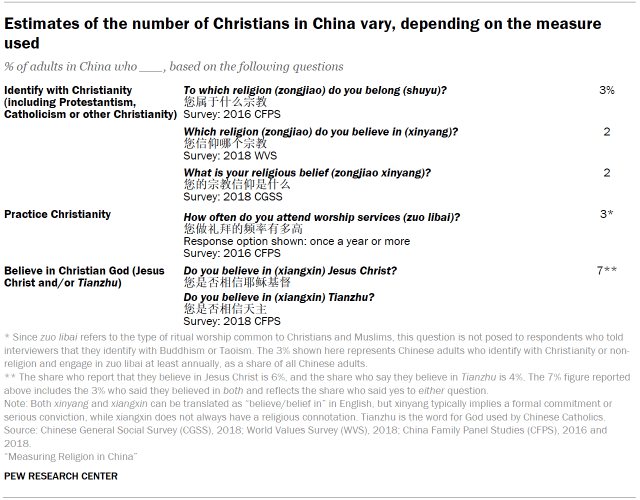

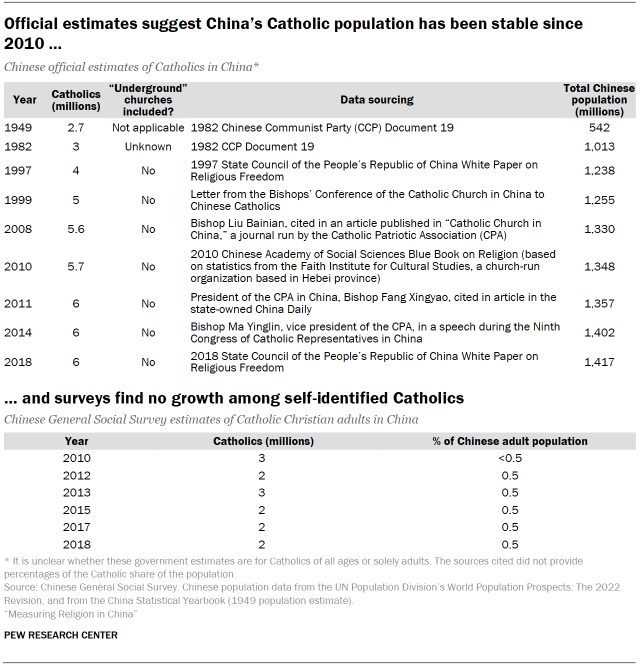

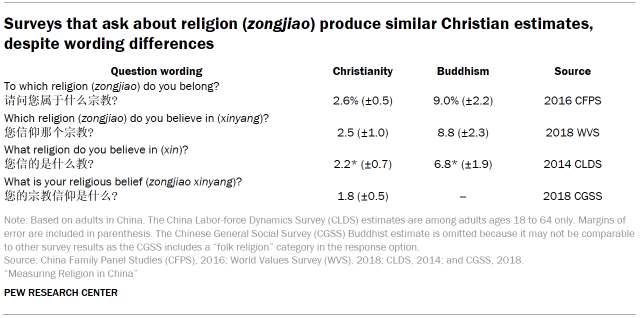

There is a range of estimates for the number of Christians in China, partly because different researchers use varying sources and methods, and partly because some analyses make adjustments to account for limitations in survey and government data.53

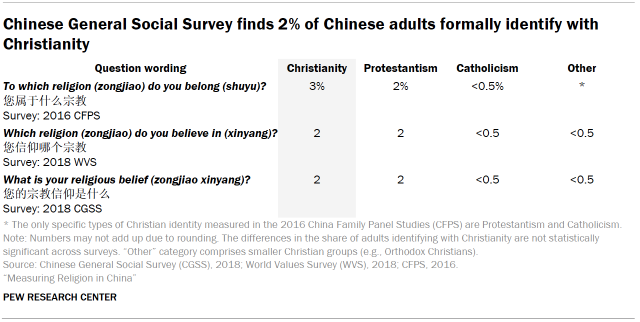

One perspective is provided by responses to the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) question “What is your religious belief (zongjiao xinyang 宗教信仰)?” In 2018, the CGSS found that roughly 2% of Chinese adults, or about 20 million people, self-identify with Christianity in this way.54 According to this survey, Protestants account for roughly 90% of Chinese Christians, or about 18 million adults, while the remainder are mostly Catholics. Smaller groups, which include Orthodox Christians, are fewer than 1% of Christian adults in China.55

Other national surveys, which use slightly different question wording, report similar shares. In the 2018 World Values Survey, 2% of Chinese adults said they believe in (xinyang 信仰) Christianity, and in the 2016 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) survey, 3% said they belong to (shuyu 属于) Christianity.

Some media reports and academic papers have suggested the Christian share may be larger, with estimates as high as 7% (100 million) or 9% (130 million) of the total population, including children. No national surveys that measure formal Christian affiliation – by asking people which religion (zongjiao) they identify with – come close to these figures.

However, survey questions that measure Christian beliefs and practices provide evidence that the number of people with some connection to Christian faith is greater than zongjiao measures reveal.

For example, the cumulative share of Chinese adults who say they “believe in” (xiangxin) Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu (天主, the word Chinese Catholics use for God) is 7%, or roughly 81 million adults, according to the 2018 CFPS survey.

Some scholars argue that this measure may be a better alternative than zongjiao xinyang, citing a core Christian teaching that one should never deny belief in God (including Jesus Christ or Tianzhu) regardless of the circumstances.56

But these figures encompass those who also believe in one or more non-Christian deities, such as Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals (Taoist deities) or Allah. The share of Chinese adults who say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu and do not believe in these other deities is about 3%.

Challenges of measuring Christianity in China

Political sensitivity

Counting Christians in China is difficult for several reasons. Officially, only churches authorized by the government are allowed to operate. But, in reality, many Christians worship in unauthorized venues known as “underground churches” (dixia jiaohui 地下教会) or “house churches” (jiating jiaohui 家庭教会). These Christians may be reluctant to reveal their identity. Likewise, members of the Chinese Communist Party, who are prohibited from holding a religious affiliation, might not disclose their Christian affiliation.57

In recent years, the government has tightened control over Christian activities outside of registered venues, banned unauthorized evangelization online, and intensified its crackdown on unauthorized Protestant meeting points and underground Catholic churches, making Christianity a very sensitive topic in China. In addition, President Xi Jinping has called for the “Sinicization of religions,” a strategy that particularly affects non-traditional belief systems, including Christianity and Islam.

(For more, read the Methodology section “Exploring the underreporting of zongjiao affiliation in Chinese surveys” and discussion of Xi Jinping’s Sinicization campaign.)

Self-identification versus belief and practice

Measuring Christianity in China is also difficult because, as discussed in other chapters, conventional measures of self-identification based on zongjiao do not fully capture the breadth of religious experience in China. And even though Christianity and Islam, unlike Buddhism or folk religions, emphasize exclusivity in belief and practice, many Chinese who engage in Christian practice or even consider themselves to be worshippers of Jesus Christ or Tianzhu may not necessarily identify with Christianity when asked about their zongjiao xinyang.

Looking cumulatively at the broadest, most inclusive survey measures of Christian affinity, as many as 8% of Chinese adults have some degree of connection to Christianity because they formally identify as Christian, believe in the Christian God or report a type of worship attendance common to Christians.

In other words, a broad approach to measuring Christian affinity generates a considerably larger estimate of the number of people with some connection to Christianity than the much smaller share who say Christianity is their zongjiao.

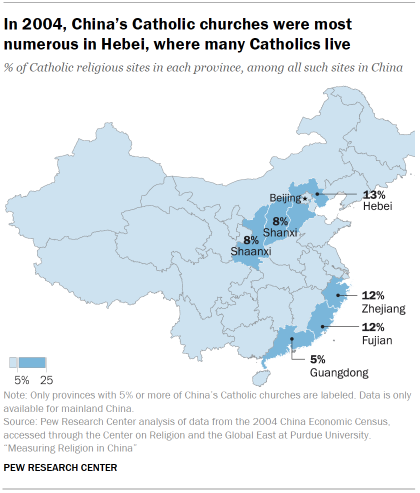

Sampling issues

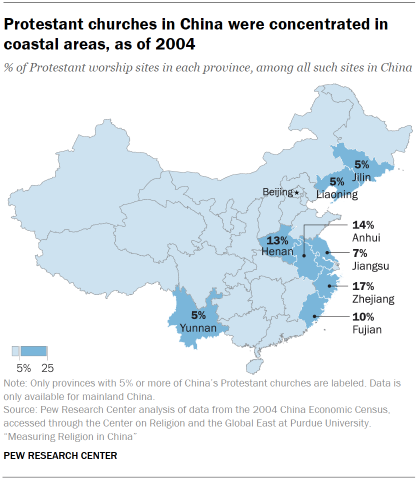

Sampling coverage, which is tied to the geographic concentration of China’s Christians, may affect the accuracy of Christian estimates. Roughly a quarter of China’s Catholics live in the northern province of Hebei, and they tend to cluster in rural “Catholic villages,” where the vast majority of residents follow Catholicism.58 As a result, Catholic survey estimates may vary depending on how many such villages are included in the sample. Similarly, it is consequential whether Protestants are proportionately represented. For example, surveys may yield a slightly lower Protestant estimate if Wenzhou – said to be the most Christian city in China – is excluded from the sample.

Some researchers argue that surveys that undersample ethnic minority groups may undercount Christians. However, the minority groups in question are relatively small in proportion to China’s population, and Bible distribution figures suggest they make up a small fraction of all Chinese Christians.59

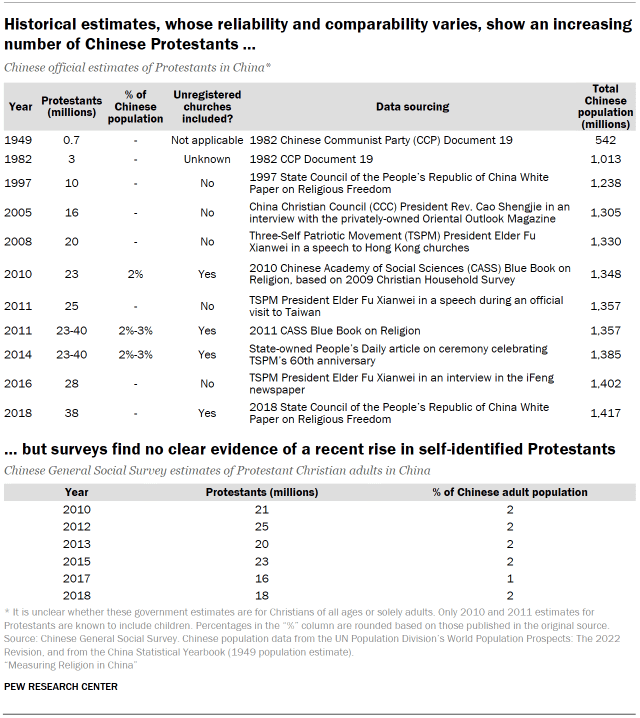

Recent change in Christian measures

Some scholars and journalists have argued in recent decades that Christianity in China is growing rapidly. Indeed, Christianity flourished after China entered an era of economic reforms and “opening up” to the world in the 1980s. But recent surveys that measure zongjiao affiliation do not offer much evidence that Christian growth continued after 2010.

According to the CGSS, about 2% of adults (23.2 million) in China self-identified as Christian in 2010, versus 2% (19.9 million) in the 2018 survey – a gap that is not statistically significant.60 (In the 2021 CGSS, 1% of respondents identified as Christian. However, this wave did not cover as many regions as previous waves of the CGSS, so the results may not be directly comparable.61)

Since measures of Christian belief and practice have not been repeated consistently in surveys, we cannot track how beliefs and practices associated with Christianity have changed since 2010 in the Chinese public. We don’t know, for example, whether overall belief in Jesus Christ or attendance at Christian worship services (zuo libai 做礼拜) has risen, declined or remained stable.

One of the few repeated survey measures of religious commitment is the broad measure of zongjiao activity, which has been included in all recent CGSS waves. Among those who identify as Christian, reports of zongjiao activity levels are roughly stable. In 2010, 38% of Christians said they engaged in zongjiao activities at least once a week, while in 2018, 35% said so – a difference that is not statistically significant.

Unfortunately, we cannot be certain how survey patterns are affected by political circumstances. There could be a real increase in the share of Chinese adults who identify with Christianity that is hidden from survey measurement. For example, it is possible there has been growth in Christian affiliation that is offset in surveys by growing reluctance among respondents to identify as Christian due to the government’s intensifying scrutiny of Christian religious activity. While that is a hypothetical possibility, there is no way to know from the available survey data whether it is actually the case.

It is also possible that the share of Christians who do not reveal their identity in surveys may have remained roughly stable since 2010. In that case, the apparent leveling off (“plateau”) in Christian identification in recent surveys could be an accurate reflection of the overall pattern, even if surveys fail to capture the full number of Chinese Christians.

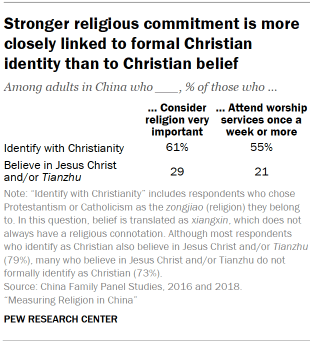

Traits associated with formal Christian affiliation

While survey questions that ask about formal zongjiao affiliation have limitations, they capture a subset of Christians who are more religious by several measures than those who say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu.

According to data from the 2016 and 2018 CFPS surveys, 68% of adults who self-identify as Christians believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu exclusively (i.e., without believing in other deities, including Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, immortals or Allah).62

By contrast, among all those who say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu, only 40% indicate they hold this belief exclusively.

Adults who formally identify with Christianity also are more likely to say religion (zongjiao) is very important in their lives than are those who say they believe in Jesus Christ and/or Tianzhu but do not necessarily formally identify with Christianity (61% vs. 29%), according to the CFPS. And they are more likely to say they attend worship services once a week or more (55% vs. 21%).

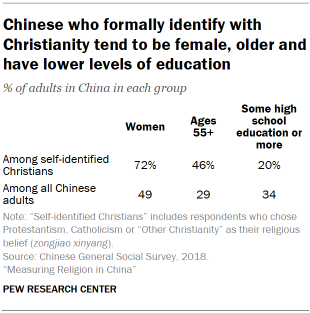

According to the 2018 CGSS, respondents who choose Christianity as their zongjiao xinyang are older and have lower educational attainment than the average Chinese adult. The majority (72%) are women.

Christian houses of worship

There are two types of officially sanctioned Protestant places of worship in China: churches (jiaotang 教堂) and meeting points (juhuidian 聚会点). A meeting point is not different from a church functionally, but it may not look like a church building; it can be an apartment or office space and usually holds fewer congregants.